August 1, 1770

Wednesday, 1st August. Strong Gales from the South-East, with Squalls attended with Rain. P.M., the Yawl came in with 2 Rays, which together weighed 265 pounds; it blow'd too hard all the time they were out for striking Turtle. Carpenters employ'd overhauling the Pumps, all of which we find in a state of decay; and this the Carpenter says is owing to the Sap having been left in, which in time has decay'd the sound wood. One of them is quite useless, and was so rotten when hoisted up as to drop to peices. However, I cannot complain of a Leaky Ship, for the most water She makes is not quite an Inch an Hour.

Banks’ Journal

1. During the Night it Blew as hard as ever; the Day was rainy with less wind but still not moderate enough for our undertakings.

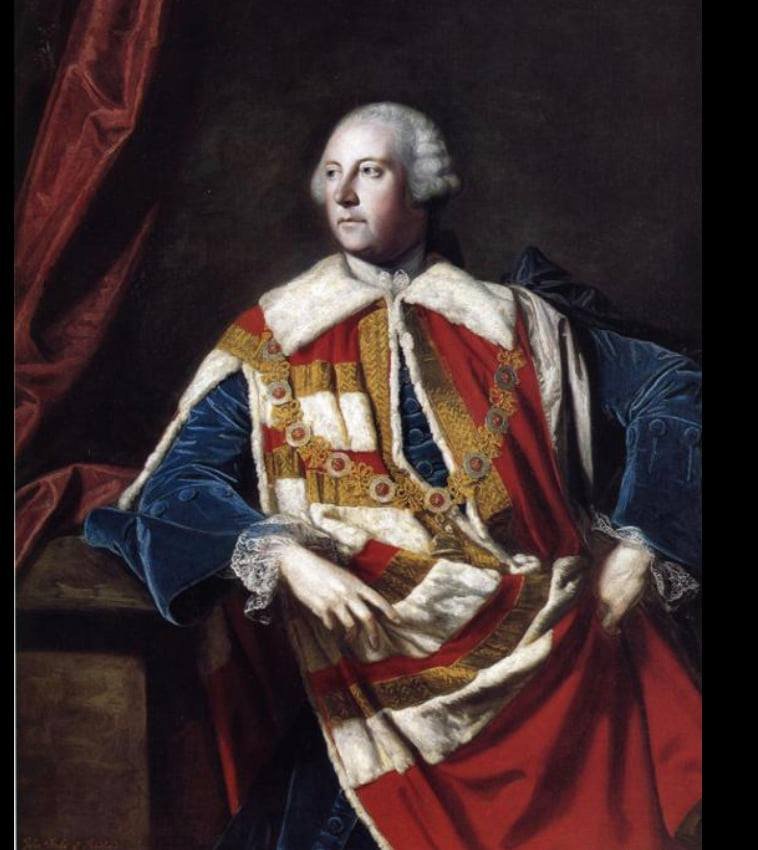

Joseph Banks by Joshua Reynolds

August 2, 1770

Thursday, 2nd. Winds and weather as yesterday, or rather more Stormy; we have now no Success in the Sein fishing, hardly getting above 20 or 30 pounds a day.

Banks’ Journal

2. Moderate and very rainy; great hopes that the Rain is a presage of approaching moderate weather.

From “Endeavour” by Peter Aughton

“Joseph Banks was a gentleman scientist and an adventurer. It says much of him that he spent three years experiencing the hardships of shipboard life with very few complaints. In later life he became president of the Royal Society.”

August 3, 1770

Endeavour Replica at Cooktown

Friday, 3rd. Strong breezes, and hazey until 6 a.m., when it moderated, and we unmoor'd, hove up the Anchor, and began to Warp out; but the Ship tailing upon the Sand on the North side of the River, the Tide of Ebb making out, and a fresh breeze setting in, we were obliged to desist and moor the Ship again just within the Barr.

Banks’ Journal

3. In the morn our people were dubious about trying to get out and I beleive delayd it rather too long. At last however they began and warpd ahead but desisted from their attempts after having ran the ship twice ashore.

Wikipedia

Warp (with reference to a ship) - move or be moved along by hauling on a rope attached to a stationary object ashore: crew and passengers helped warp the vessels through the shallow section.

Description of Endeavour River

I shall now give a Short description of the Harbour, or River, we have been in, which I named after the Ship, Endeavour River. It is only a small Barr Harbour or Creek, which runs winding 3 or 4 Leagues in land, at the Head of which is a small fresh Water Brook, as I was told, for I was not so high myself; but there is not water for Shipping above a Mile within the barr, and this is on the North side, where the bank is so steep for nearly a quarter of a Mile that ships may lay afloat at low water so near the Shore as to reach it with a stage, and is extreamly Convenient for heaving a Ship down. And this is all the River hath to recommend it, especially for large Shipping, for there is no more than 9 or 10 feet Water upon the Bar at low water, and 17 or 18 feet at high, the Tides rises and falling about 9 feet at spring Tide, and is high on the days of the New and full Moon, between 9 and 10 o'Clock. Besides, this part of the Coast is barrocaded with Shoals, as to make this Harbour more difficult of access; the safest way I know of to come at it is from the South, Keeping the Main land close on board all the way. Its situation may always be found by the Latitude, which hath been before mentioned. Over the South point is some high Land, but the North point is formed by a low sandy beach, which extends about 3 Miles to the Northward, then the land is again high.

The refreshments we got here were Chiefly Turtle, but as we had to go 5 Leagues out to Sea for them, and had much blowing weather, we were not over Stocked with this Article; however, what with these and the fish we caught with the Sean we had not much reason to Complain, considering the Country we were in. Whatever refreshment we got that would bear a Division I caused to be equally divided among the whole Company, generally by weight; the meanest person in the Ship had an equal share with myself or any one on board, and this method every commander of a Ship on such a Voyage as this ought ever to Observe. We found in several places on the Sandy beaches and Sand Hills near the Sea, Purslain and beans, which grows on a Creeping kind of a Vine. The first we found very good when boiled, and the latter not to be dispised, and were at first very serviceable to the Sick; but the best greens we found here was the Tarra, or Coco Tops, called in the West Indies Indian Kale [Colocasia Macrorhiza] which grows in most Boggy Places; these eat as well as, or better, than Spinnage. The roots, for want of being Transplanted and properly Cultivated, were not good, yet we could have dispensed with them could we have got them in any Tolerable plenty; but having a good way to go for them, it took up too much time and too many hands to gather both root and branch. The few Cabage Palms we found here were in General small, and yielded so little Cabage that they were not worth the Looking after, and this was the Case with most of the fruit, etc., we found in the woods.

Besides the Animals which I have before mentioned, called by the Natives Kangooroo, or Kanguru, here are Wolves [probably Dingos], Possums, an Animal like a ratt, and snakes, both of the Venemous and other sorts. Tame Animals here are none except Dogs, and of these we never saw but one, who frequently came about our Tents to pick up bones, etc. The Kanguru are in the greatest number, for we seldom went into the Country without seeing some. The land Fowls we met here, which far from being numerous, were Crows, Kites, Hawkes, Cockadores [Cockatoos] of 2 Sorts, the one white, and the other brown, very beautiful Loryquets of 2 or 3 Sorts, Pidgeons, Doves, and a few other sorts of small Birds. The Sea or Water fowl are Herns, Whisling Ducks, which perch and, I believe, roost on Trees; Curlews, etc., and not many of these neither. Some of our Gentlemen who were in the Country heard and saw Wild Geese in the Night.

The Country, as far as I could see, is diversified with Hills and plains, and these with woods and Lawns; the Soil of the Hills is hard, dry, and very Stoney; yet it produceth a thin Coarse grass, and some wood. The Soil of the Plains and Valleys are sandy, and in some places Clay, and in many Parts very Rocky and Stoney, as well as the Hills, but in general the Land is pretty well Cloathed with long grass, wood, Shrubs, etc. The whole Country abounds with an immense number of Ant Hills, some of which are 6 or 8 feet high, and more than twice that in Circuit. Here are but few sorts of Trees besides the Gum tree, which is the most numerous, and is the same that we found on the Southern Part of the Coast, only here they do not grow near so large. On each side of the River, all the way up it, are Mangroves, which Extend in some places a Mile from its banks; the Country in general is not badly water'd, there being several fine Rivulets at no very great distance from one another, but none near to the place where we lay; at least not in the Dry season, which is at this time. However we were very well supply'd with water by springs which were not far off. [Cooktown, which now stands on the Endeavour River, is a thriving place, and the northernmost town on this coast. It has some 2000 inhabitants, and is the port for a gold mining district. A deeper channel has now been dredged over the bar that gave Cook so much trouble, but it is not a harbour that will admit large vessels]

Comments in [ ] are by W J L Wharton in April 1893

August 4 1770

Finally, Cook leaves the Endeavour River

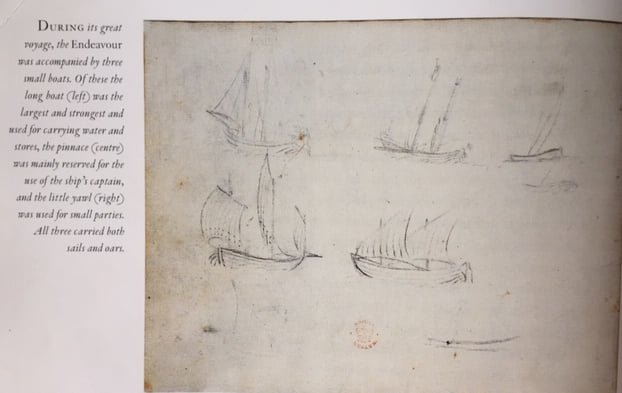

Saturday, 4th. In the P.M., having pretty moderate weather, I order'd the Coasting Anchor and Cable to be laid without the barr, to be ready to warp out by, that we might not loose the least opportunity that might Offer; for laying in Port spends time to no purpose, consumes our Provisions, of which we are very Short in many Articles, and we have yet a long Passage to make to the East Indies through an unknown and perhaps dangerous Sea; these Circumstances consider'd, make me very Anxious of getting to Sea. The wind continued moderate all night, and at 5 a.m. it fell calm; this gave us an opportunity to warp out. About 7 we got under sail, having a light Air from the Land, which soon died away, and was Succeeded by the Sea breezes from South-East by South, with which we stood off to Sea East by North, having the Pinnace ahead sounding. The Yawl I sent to the Turtle bank to take up the Net that was left there; but as the wind freshen'd we got out before her, and a little After Noon Anchor'd in 15 fathoms water, Sandy bottom, for I did not think it safe to run in among the Shoals until I had well view'd them at low Water from the Mast head, that I might be better Able to Judge which way to Steer; for as yet I had not resolved whether I should beat back to the Southward round all the Shoals, or seek a Passage to the Eastward or Northward, all of which appeared to be equally difficult and dangerous. When at Anchor the Harbour sail'd from bore South 70 degrees West, distant 4 or 5 Leagues; the Northermost point of the Main land we have in sight, which I named Cape Bedford [Probably after John, 4th Duke, who had been First Lord of the Admiralty, 1744 to 1747] but we could see land to the North-East of this Cape, which made like 2 high Islands [Direction Islands]; the Turtle banks bore East, distant one Mile. Latitude by Observation 15 degrees 23 minutes South; our depth of Water, in standing off from the land, was from 3 1/2 to 15 fathoms

Banks’ Journal

4. Fine calm morn. Began early and warp'd the ship out, after which we saild right out till we came to the turtle reef where our turtlers took one turtle. Myself got some few shells but saw many Beautifull sea insects &c. At night our people who fishd caught abundance of sharks.

Wikipedia

John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford (30 September 1710 – 5 January 1771) was an 18th-century British statesman. He was the fourth son of Wriothesley Russell, 2nd Duke of Bedford, by his wife, Elizabeth. Known as Lord John Russell, he married in October 1731 Diana Spencer, daughter of Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland; became Duke of Bedford on his brother's death a year later;

Portrait of the Duke of Bedford by Joshua Reynolds

August 5, 1770

At Anchor, Off Turtle Reef, Queensland

Sunday, 5th. In the P.M. had a Gentle breeze at South-East and Clear weather. As I did not intend to weigh until the morning I sent all the Boats to the Reef to get what Turtle and Shell fish they could. At low water from the Mast head I took a view of the Shoals, and could see several laying a long way without this one, a part of several of them appearing above water; but as it appear'd pretty clear of Shoals to the North-East of the Turtle Reef, I came to a Resolution to stretch out that way close upon a wind, because if we found no Passage we could always return back the way we went. In the Evening the Boats return'd with one Turtle, a sting ray, and as many large Clams as came to 1 1/2 pounds a Man; in each of these Clams were about 20 pounds of Meat; added to this we Caught in the night several Sharks. Early in the morning I sent the Pinnace and Yawl again to the Reef, as I did not intend to weigh until half Ebb, at which time the Shoals began to appear. Before 8 it came on to blow, and I made the Signal for the Boats to come on Board, which they did, and brought with them one Turtle. We afterwards began to heave, but the wind Freshening obliged us to bear away [To veer cable, i.e. pay out more cable, in order to hold the ship with the freshening wind] again and lay fast.

Banks’ Journal

5. The Turtlers were again out upon the shoal and took one turtle. At 2 we weighd, resolvd to stand out as well as we could among the shoals, but before night were stoppd by another shoal which lay directly across our way.

August 6 1770

Monday, 6th. Winds at South-East. At 2 o'Clock p.m. it fell pretty Moderate, and we got under sail, and stood out upon a wind North-East by East, leaving the Turtle Reef to windward, having the Pinnace ahead sounding. We had not stood out long before we discovered shoals ahead and on both bows. At half past 4 o'Clock, having run off 8 Miles, the Pinnace made the Signal for Shoal water in a place where we little Expected it; upon this we Tack'd and Stood on and off while the Pinnace stretched farther to the Eastward, but as night was approaching I thought it safest to Anchor, which we accordingly did in 20 fathoms water, a Muddy bottom. Endeavour River bore South 52 degrees West; Cape Bedford West by North 1/2 North, distant 5 Leagues; the Northermost land in sight, which made like an Island, North; and a Shoal, a small, sandy part of which appear'd above water, North-East, distance 2 or 3 Miles. In standing off from this Turtle Reef to this place our soundings were from 14 to 20 fathoms, but where the Pinnace was, about a Mile farther to the East-North-East, were no more than 4 or 5 feet of water, rocky ground; and yet this did not appear to us in the Ship. In the morning we had a strong Gale from the South-East, that, instead of weighing as we intended, we were obliged to bear away more Cable, and to Strike Top Gallant yards.

Banks’ Journal

6. Blew so fresh that we could not move but lay still all day, not without anxiety least the anchor should not hold.

W J L Wharton wrote in his Introduction to Cook’s Journal in 1893:

It was the usual custom on board ships to keep what was known as Ship time—i.e., the day began at noon BEFORE the civil reckoning, in which the day commences at midnight. Thus, while January 1st, as ordinarily reckoned, is from midnight to midnight, in ship time it began at noon on December 31st and ended at noon January 1st, this period being called January 1st. Hence the peculiarity all through the Journal of the p.m. coming before the a.m. It results that any events recorded as occurring in the p.m. of January 1st in the log, would, if translated into the ordinary system, be given as happening in the p.m. of December 31st; while occurrences in the a.m. of January 1st would be equally in the a.m. of January 1st in both systems.

Wikipedia

In oceanography, geomorphology, and earth sciences, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material, and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface

August 7, 1770

Tuesday, 7th. Strong Gales at South-East, South-East by South, and South-South-East, with cloudy weather at Low water in the P.M. I and several of the Officers kept a look out at the Mast head to see for a Passage between the Shoals; but we could see nothing but breakers all the way from the South round by the East as far as North-West, extending out to Sea as far as we could see. It did not appear to be one continued Shoal, but several laying detached from each other. On the Eastermost that we could see the Sea broke very high, which made one judge it to be the outermost; for on many of those within the Sea did not break high at all, and from about 1/2 flood to 1/2 Ebb they are not to be seen, which makes the Sailing among them more dangerous, and requires great care and Circumspection, for, like all other Shoals, or Reefs of Coral Rocks, they are quite steep too. Altho' the most of these Shoals consist of Coral Rocks, yet a part of some of them is sand. The Turtle Reef and some others have a small Patch of Sand generally at the North end, that is only cover'd at high water. These generally discover themselves before we come near them. Altho' I speak of this as the Turtle Reef, yet it is not to be doubted but what there are Turtle upon the most of them as well as this one. After having well viewed our situation from the Mast Head, I saw that we were surrounded on every side with Dangers, in so much that I was quite at a loss which way to steer when the weather will permit us to get under sail, for to beat back to the South-East the way we came, as the Master would have had me done, would be an endless peice of work, as the winds blow constantly from that Quarter, and very Strong, without hardly any intermission; [The south-east trade wind blows home on this coast very strong from about June to October. Though the Barrier Reef prevents any great sea from getting up, the continuance of this wind is a great nuisance for a sailing ship from many points of view though from others it is an advantage.] on the other hand, if we do not find a passage to the Northward we shall have to come back at last. At 11 the Ship drove, and obliged us to bear away to a Cable and one third, which brought us up again; but in the morning the Gale increasing, she drove again. This made us let go the Small Bower Anchor, and bear away a whole Cable on it and 2 on the other; and even after this she still kept driving slowly, until we had got down Top gallant Masts, struck Yards and Top masts close down, and made all snug; then she rid fast, Cape Bedford bearing West-South-West, distant 3 1/2 Leagues. In this situation we had Shoals to the Eastward of us extending from the South-East by South to the North-North-West, distant from the nearest part of them about 2 Miles.

Banks’ Journal

7. During last night the gale had freshned much and in the morn we found that we had Drove above a League. Fortunately no shoal had in that distance taken us up but one was in sight astern and the ship drove fast towards it, on this another anchor was let go and much cable verd out but even this would not stop her. Our prospect was now more melancholy than ever: the shoal was plainly to be seen and the ship still driving gently down towards it, a sea running at the same time which would make it impossible ever to get off if we should be unfortunate enough to get on. Yards and Topmasts were therefore got down and every thing done which could be thought of to make the ship snug, without any effect: she still drove and the shoal we dreaded came nearer and nearer to us. The sheet anchor our last resource was now thought of and prepard, but fortunately for us before we were drove to the making use of that expedient the ship stoppd and held fast, to our great joy. During the time of its blowing yesterday and today we became certain that between us and the open sea was a ledge of rocks or reef just the same as we had seen at the Islands, no very agreable discovery, for should that at any time join in with the main land we must wait for another season when different winds from the present ones prevaild; in which case we must infallibly be short of provisions or, if the turtle should fail us, Salt provisions without bread was all we had to trust to.

August 8, 1770

Wednesday, 8th. Strong gales at South-South-East all this day, in so much that I durst not get up Yards and Topmasts.

Banks’ Journal

8. The night Dark as pitch passd over not without much anxiety: whether our anchors held or not we could not tell and maybe might when we least thought of it be upon the very brink of destruction. Day light however releivd us shewd us that the anchors had held and also brought us rather more moderate weather, so that towards evening we venturd to get up Yards and top masts.

August 9, 1770

Thursday, 9th. In the P.M., the weather being something moderate, we got up the Top masts, but keept the Lower yards down. At 6 in the morning we began to heave in the Cable, thinking to get under sail; but it blow'd so fresh, together with a head sea, that we could hardly heave the ship a head, and at last was obliged to desist.

Banks’ Journal

9. Night and morning still more moderate so that one anchor was got up and we had great hopes of sailing on the next morn.

August 10 1770

Off Cape Flattery, Queensland

Friday, 10th. Fresh Gales at South-South-East and South-East by South. P.M., the wind fell so that we got up the small Bower Anchor, and hove into a whole Cable on the Best Bower. At 3 in the morning we got up the Lower Yards, and at 7 weighed and stood in for the Land (intending to seek for a passage along Shore to the northward), having a Boat ahead sounding; depth of water as we run in from 19 to 12 fathoms. After standing in an hour we edged away for 3 Small Islands [Now called the Three Isles] that lay North-North-East 1/2 East, 3 Leagues from Cape Bedford. To these Islands the Master had been in the Pinnace when the Ship was in Port. At 9 we were abreast of them, and between them and the Main, having another low Island between us and the latter, which lies West-North-West, 4 Miles from the 3 Islands. In this Channell had 14 fathoms water; the Northermost point of the Main we had in sight bore from us North-North-West 1/2 West, distant 2 Leagues. 4 or 5 Leagues to the North-East of this head land appeared 3 high Islands [the Direction Islands] with some smaller ones near them, and the Shoals and Reefs without, as we could see, extending to the Northward as far as these Islands. We directed our Course between them and the above headland, leaving a small Island [the Two Isles. Cook had now got among the numerous islands and reefs which lie round Cape Flattery. There are good channels between them, but they are very confusing to a stranger. Cook's anxiety in his situation can well be imagined, especially with his recent disaster in his mind] to the Eastward of us, having all the while a boat ahead sounding. At Noon we were got between the head Land and the 3 high Islands, distant from the former 2, and from the latter 4 Leagues; our Latitude by observation was 14 degrees 51 minutes South. We now judged ourselves to be clear of all Danger, having, as we thought, a Clear, open Sea before us; but this we soon found otherwise, and occasioned my calling the Headland above mentioned Cape Flattery (Latitude 14 degrees 55 minutes South, Longitude 214 degrees 43 minutes West). It is a high Promontory, making in 2 Hills next the sea, and a third behind them, with low sandy land on each side; but it is better known by the 3 high Islands out at Sea, the Northermost of which is the Largest, and lies from the Cape North-North-East, distant 5 Leagues. From this Cape the Main land trends away North-West and North-West by West.

Banks’ Journal

10. Fine weather so the anchor was got up and we saild down to leward, convincd that we could not get out the way we had tried before and hoping there might be a passage that way: in these hopes we were much encouraged by the sight of some high Islands where we hopd the shoals would end. By 12 we were among these and fancied that the grand or outer reef ended on one of them so were all in high spirits, but about dinner time the people at the mast head saw as they thought Land all round us, on which we immediatedly came to an anchor resolvd to go ashore and from the hills examine whether it was so or not.

The point we went upon was sandy and very Barren so it affforded very few plants or any thing else worth our observation. The Sand itself indeed with which the whole countrey in a manner was coverd was infinitely fine and white, but till a glass house was built here that would turn to no account. We had the satisfaction however to see that what was taken for land round us provd only a number of Islands: to one very high one about 5 leagues from the Land the Captain resolvd to go in the Boat tomorrow in order to see whether the grand reef had realy left us or not.

Wikipedia

Cape Flattery is the location of the world's biggest silica mine. The mine was established in 1967 and was severely damaged by Cyclone Ita in 2014.

The cape's local port is used for the shipping of silica sand from a local subsidiary of Mitsubishi Corporation, and exports the most silica sand internationally, with 1.7 million tonnes exported alone in 2007–08.

August 11, 1770

Saturday, 11th. Fresh breezes at South-South-East and South-East by South, with which we steer'd along shore North-West by West until one o'Clock, when the Petty Officer at the Masthead called out that he saw land ahead, extending quite round to the Islands without, and a large reef between us and them; upon this I went to the Masthead myself. The reef I saw very plain, which was now so far to windward that we could not weather it, but what he took for Main land ahead were only small Islands, for such they appeared to me; but, before I had well got from Mast head the Master and some others went up, who all asserted that it was a Continuation of the Main land, and, to make it still more alarming, they said they saw breakers in a Manner all round us. We immediately hauld upon a wind in for the Land, and made the Signal for the Boat, which was ahead sounding, to come on board; but as she was well to leeward, we were obliged to edge away to take her up, and soon after came to an Anchor under a point of the Main in 1/4 less 5 [The nautical manner of expressing four and three-quarters] fathoms, about a Mile from the Shore, Cape Flattery bearing South-East, distant 3 1/2 Leagues. After this I landed, and went upon the point, which is pretty high, from which I had a View of the Sea Coast, which trended away North-West by West, 8 or 10 Leagues, which was as far as I could see, the weather not being very clear. I likewise saw 9 or 10 Small, Low Islands and some Shoals laying off the Coast, and some large Shoals between the Main and the 3 high Islands, without which, I was now well assured, were Islands, and not a part of the Mainland as some had taken them to be. Excepting Cape Flattery and the point I am now upon, which I have named point Lookout, the Main land next the sea to the Northward of Cape Bedford is low, and Chequer'd with white sand and green Bushes, etc., for 10 or 12 Miles inland, beyond which is high land. To the northward of Point Lookout the shore appear'd to be shoal and flat some distance off, which was no good sign of meeting with a Channell in with the land, as we have hitherto done. We saw the footsteps of people upon the sand, and smoke and fire up in the Country, and in the evening return'd on board, where I came to a resolution to visit one of the high Islands in the Offing in my Boat, as they lay at least 5 Leagues out at Sea, and seem'd to be of such a height that from the Top of one of them I hoped to see and find a Passage out to sea clear of the Shoals. Accordingly in the Morning I set out in the Pinnace for the Northermost and largest of the 3, accompanied by Mr. Banks. At the same time I sent the Master in the Yawl to Leeward, to sound between the Low Islands and the Main. In my way to the Island I passed over a large reef of Coral Rocks and sand, which lies about 2 Leagues from the Island; I left another to leeward, which lays about 3 Miles from the Island. [On Lizard Island, Queensland.] On the North part of this is a low, sandy Isle, with Trees upon it; on the reef we pass'd over in the Boat we saw several Turtle, and Chased one or Two, but caught none, it blowing too hard, and I had no time to spare, being otherways employ'd. I did not reach the Island until half an hour after one o'Clock in the P.M. on (Sunday).

Banks’ Journal

11. As propos'd yesterday the Captn went today to the Island which provd 5 leagues off from the ship, I went with him. In going out we passd over 2 very large shoals on which we saw great plenty of Turtle but we had too much wind to strike any. The Island itself was high; we ascended the hill and when we were at the top saw plainly the Grand Reef still extending itself Paralel with the shore at about the distance of 3 leagues from us or 8 from the main; through it were several channels exactly similar to those we had seen in the Islands. Through one of these we determind to [go] which seemd most easy: to ascertain however the Practicability of it We resolvd to stay upon the Island all night and at day break in the morn send the boat to sound one of them, which was accordingly done. We slept under the shade of a Bush that grew on the Beach very comfortably.

August 12 1770

Sunday, 12th, when I immediately went upon the highest hill on the Island [Lizard Island] where, to my Mortification, I discover'd a Reef of Rocks laying about 2 or 3 Leagues without the Island, extending in a line North-West and South-East, farther than I could see, on which the sea broke very high. [This was the outer edge of the Barrier Reefs] This, however, gave one great hopes that they were the outermost shoals, as I did not doubt but what I should be able to get without them, for there appeared to be several breaks or Partitions in the Reef, and Deep Water between it and the Islands. I stay'd upon the Hill until near sun set, but the weather continued so Hazey all the time that I could not see above 4 or 5 Leagues round me, so that I came down much disappointed in the prospect I expected to have had, but being in hopes the morning might prove Clearer, and give me a better View of the Shoals. With this view I stay'd all night upon the Island, and at 3 in the Morning sent the Pinnace, with one of the Mates I had with me, to sound between the Island and the Reefs, and to Examine one of the breaks or Channels; and in the mean time I went again upon the Hill, where I arrived by Sun Rise, but found it much Hazier than in the Evening. About Noon the pinnace return'd, having been out as far as the Reef, and found from 15 to 28 fathoms water. It blow'd so hard that they durst not venture into one of the Channels, which, the Mate said, seem'd to him to be very narrow; but this did not discourage me, for I thought from the place he was at he must have seen it at disadvantage. Before I quit this Island I shall describe it. It lies, as I have before observed, about 5 Leagues from the Main; it is about 8 Miles in Circuit, and of a height sufficient to be seen 10 or 12 Leagues; it is mostly high land, very rocky and barren, except on the North-West side, where there are some sandy bays and low land, which last is covered with thin, long grass, Trees, etc., the same as upon the Main. Here is also fresh Water in 2 places; the one is a running stream, the water a little brackish where I tasted it, which was close to the sea; the other is a standing pool, close behind the sandy beach, of good, sweet water, as I daresay the other is a little way from the Sea beach. The only land Animals we saw here were Lizards, and these seem'd to be pretty Plenty, which occasioned my naming the Island Lizard Island. The inhabitants of the Main visit this Island at some Seasons of the Year, for we saw the Ruins of Several of their Hutts and heaps of Shells, etc. South-East, 4 or 5 Miles from this Island, lay the other 2 high Islands, which are very small compared to this; and near them lay 3 others, yet smaller and lower Islands, and several Shoals or reefs, especially to the South-East. There is, however, a clear passage from Cape Flattery to those Islands, and even quite out to the outer Reefs, leaving the above Islands to the South-East and Lizard Island to the North-West.

Banks’ Journal

12. Great Part of yesterday and all this morn till the boat returnd I employd in searching the Island. On it I found some few plants which I had not before seen; the Island itself was small and Barren; on it was however one small tract of woodland which abounded very much with large Lizzards some of which I took. Distant as this Isle was from the main, the Indians had been here in their poor embarkations, sure sign that some part of the year must have very setled fine weather; we saw 7 or 8 frames of their huts and vast piles of shells the fish of which had I suppose been their food. All the houses were built upon the tops of Eminences exposd intirely to the SE, contrary to those of the main which are commonly placd under the shelter of some bushes or hill side to break off the wind. The officer who went in the Boat returnd with an account that the sea broke vastly high upon the reef and the swell was so great in the opening that he could not go into it to sound. This was sufficient to assure us of a safe passage out, so we got into the boat to return to the ship in high spirits, thinking our danger now at an end as we had a passage open for us to the main Sea. In our return we went ashore upon a low Island where we shot many birds; on it was an Eagles nest the young ones of which we killd, and another built on the ground by I know not what bird, of a most enormous magnitude - it was in circumference 26 feet and in hight 2 feet 8 built of sticks; the only Bird I have seen in this countrey capable of building such a nest seems to be the Pelecan. The Indians have been here likewise and livd upon turtle, as we could plainly see by the heaps of Callipashes which were pild up in several parts of the Island. Our Master who had been sent to leward to examine that Passage went ashore upon a low Island where he slept. Here he saw vast plenty of turtle shells, and so great plenty had the Indians had when there that they had hung up the finns with the meat left on them in trees, where the sun had dryd them so well that our seamen eat them heartily. He saw also two spots clear of grass which had lately been dug up; they were about 7 feet long and shaped like a grave, for which indeed he took them.

Callipash - the greenish glutinous edible part of the turtle found next to the upper shell, considered a delicacy (Source / Collins English Dictionary). Perhaps changed from Spanish carapacho CARAPACE

August 13, 1770

Monday, 13th. At 2 P.M. I left Lizard Island in order to return to the Ship, and in my way landed upon the low sandy Isle mentioned in coming out. We found on this Island [Eagle Island] a pretty number of Birds, the most of them sea Fowl, except Eagles; 2 of the Latter we shott and some of the others; we likewise saw some Turtles, but got none, for the reasons before mentioned. After leaving Eagle Isle I stood South-West direct for the Ship, sounding all the way, and had not less than 8 fathoms, nor more than 14. I had the same depth of Water between Lizard and Eagle Isle. After I got on board the Master inform'd me he had been down to the Islands I had directed him to go too, which he judged to lay about 3 Leagues from the Main, and had sounded the Channel between the 2, found 7 fathoms; this was near the Islands, for in with the Main he had only 9 feet 3 Miles off, but without the Islands he found 10, 12, and 14 fathoms. He found upon the islands piles of turtle shells, and some finns that were so fresh that both he and the boats' crew eat of them. This showed that the natives must have been there lately. After well considering both what I had seen myself and the report of the Master's, I found by experience that by keeping in with the Mainland we should be in continued danger, besides the risk we should run in being lock'd in with Shoals and reefs by not finding a passage out to Leeward. In case we persever'd in keeping the Shore on board an accident of this kind, or any other that might happen to the ship, would infallibly loose our passage to the East India's this Season [In November the wind changes to the North-West, which would have been a foul wind to Batavia] and might prove the ruin of both ourselves and the Voyage, as we have now little more than 3 Months' Provisions on board, and that at short allowance. Wherefore, after consulting with the Officers, I resolved to weigh in the morning, and Endeavour to quit the Coast altogether until such time as I found I could approach it with less danger. With this View we got under sail at daylight in the morning, and stood out North-East for the North-West end of Lizard Island, having Eagle Island to windward of us, having the pinnace ahead sounding; and here we found a good Channell, wherein we had from 9 to 14 fathoms. At Noon the North end of Lizard Island bore East-South-East, distant one Mile; Latitude observed 14 degrees 38 minutes South; depth of water 14 fathoms. We now took the pinnace in tow, knowing that there were no dangers until we got out to the Reefs. [ From the 13th to the 19th the language used in Mr. Corner's copy of the Journal is quite different from that of the Admiralty and the Queen's, though the occurrences are the same. From internal evidences, it appears that Mr. Corner's copy was at this period the first written up, and that Cook amended the phrases in the other fair copies.]

Banks’ Journal

13. Ship stood out for the opening we had seen in the reef and about 2 O'Clock passd it. It was about _ a mile wide. As soon as the ship was well without it we had no ground with100 fathm of Line so became in an instant quite easy, being once more in the main Ocean and consequently freed from all our fears of shoals &c.

Wikipedia

Eagle Island is in a national park in Queensland, Australia, 692 km north-west of Brisbane. The island is part of the Lizard Island Group and is south of Lizard Island situated 270 km north of Cairns, Queensland.

August 14, 1770

Pass Outside Barrier Reef, Queensland

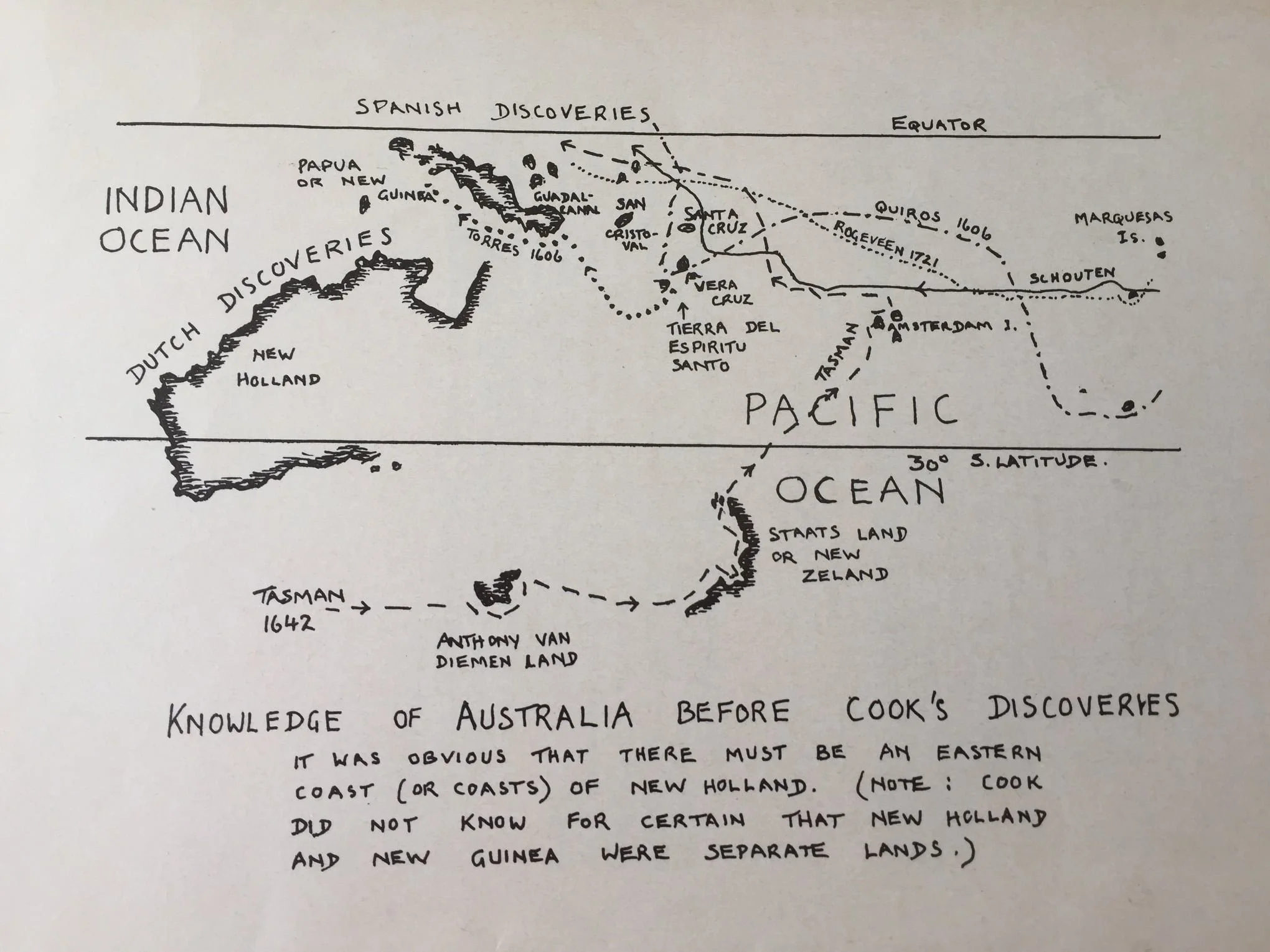

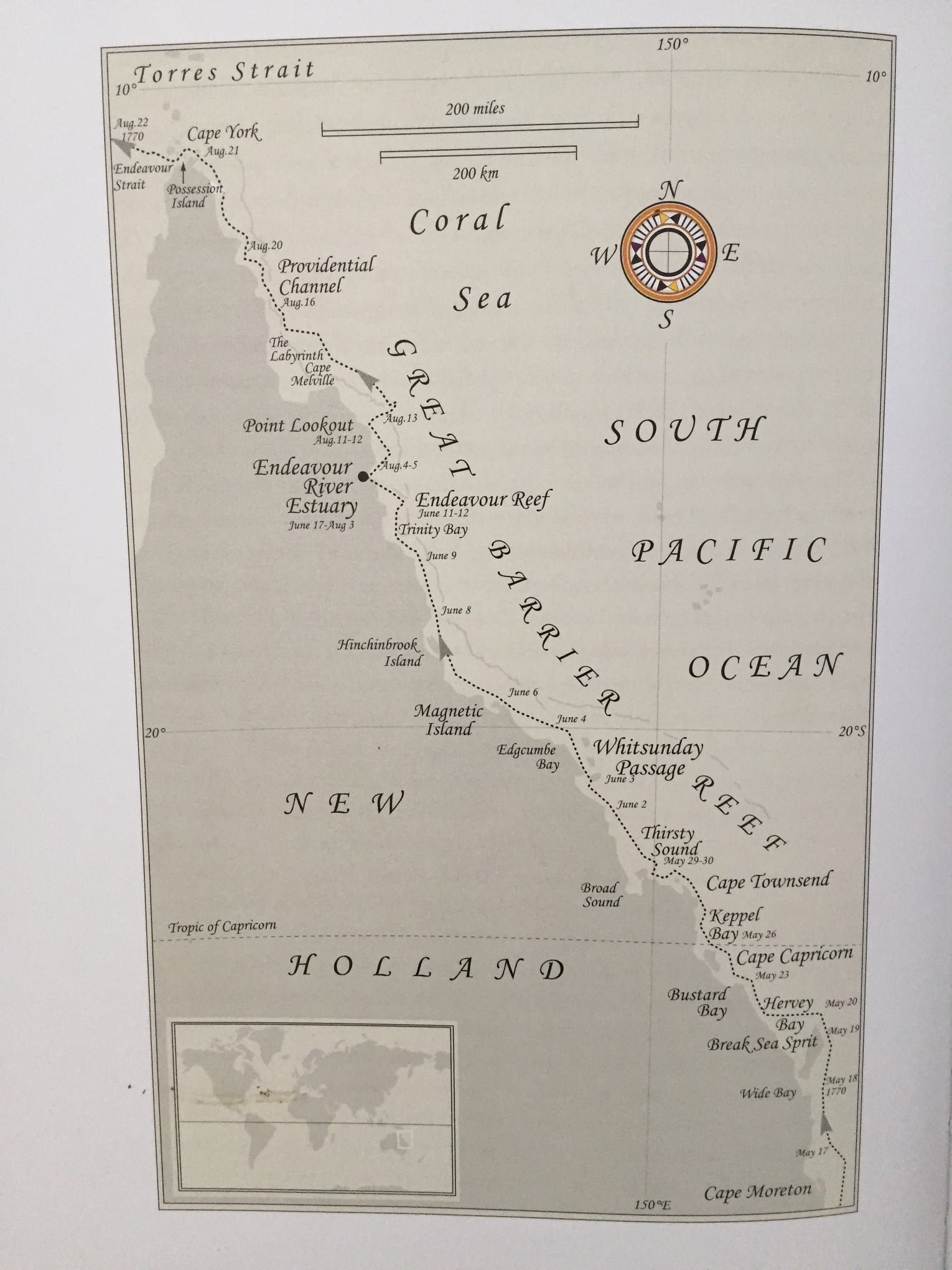

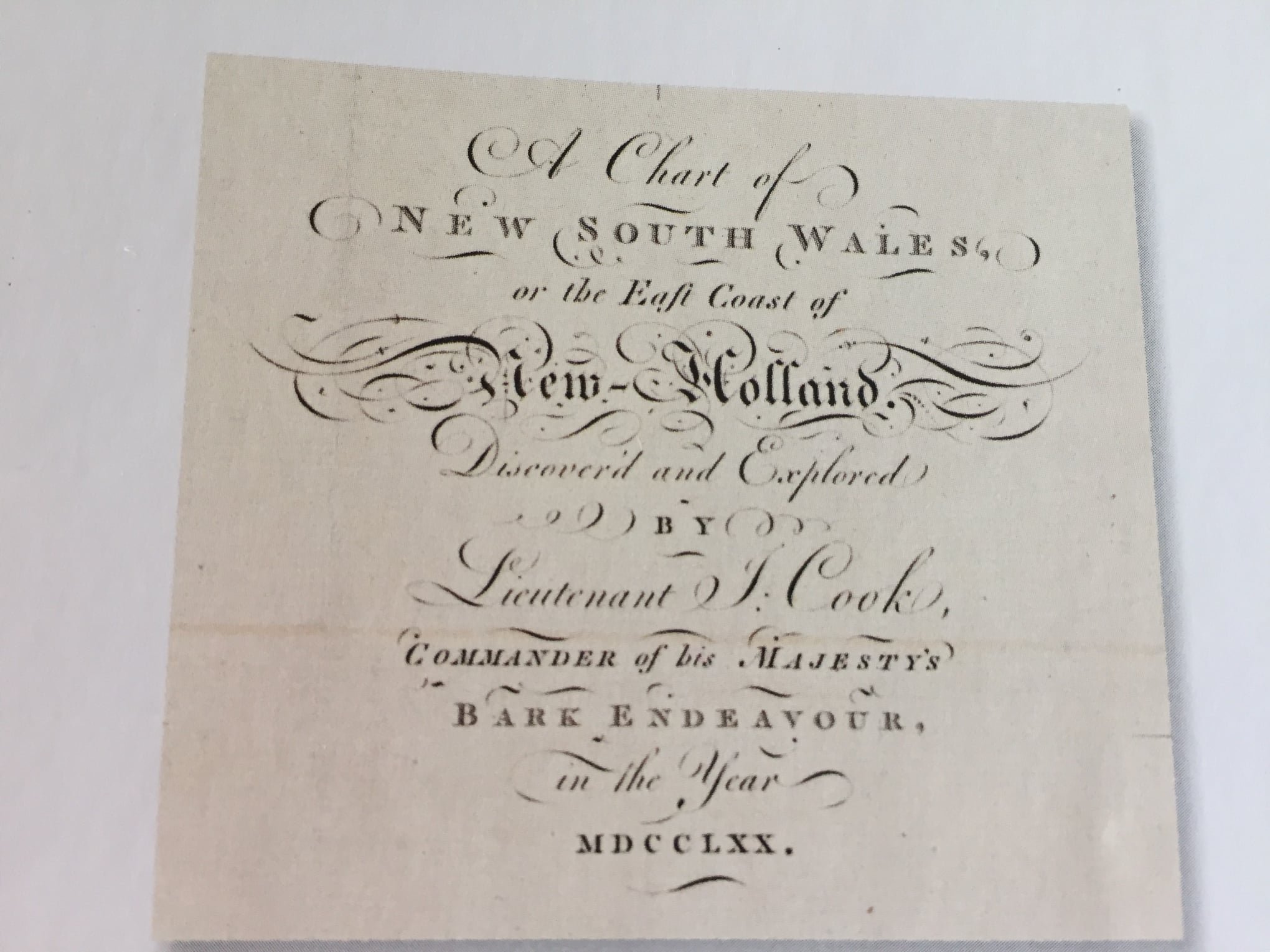

Map from “Captain Cook’s Australian landfalls” by W D Forsyth

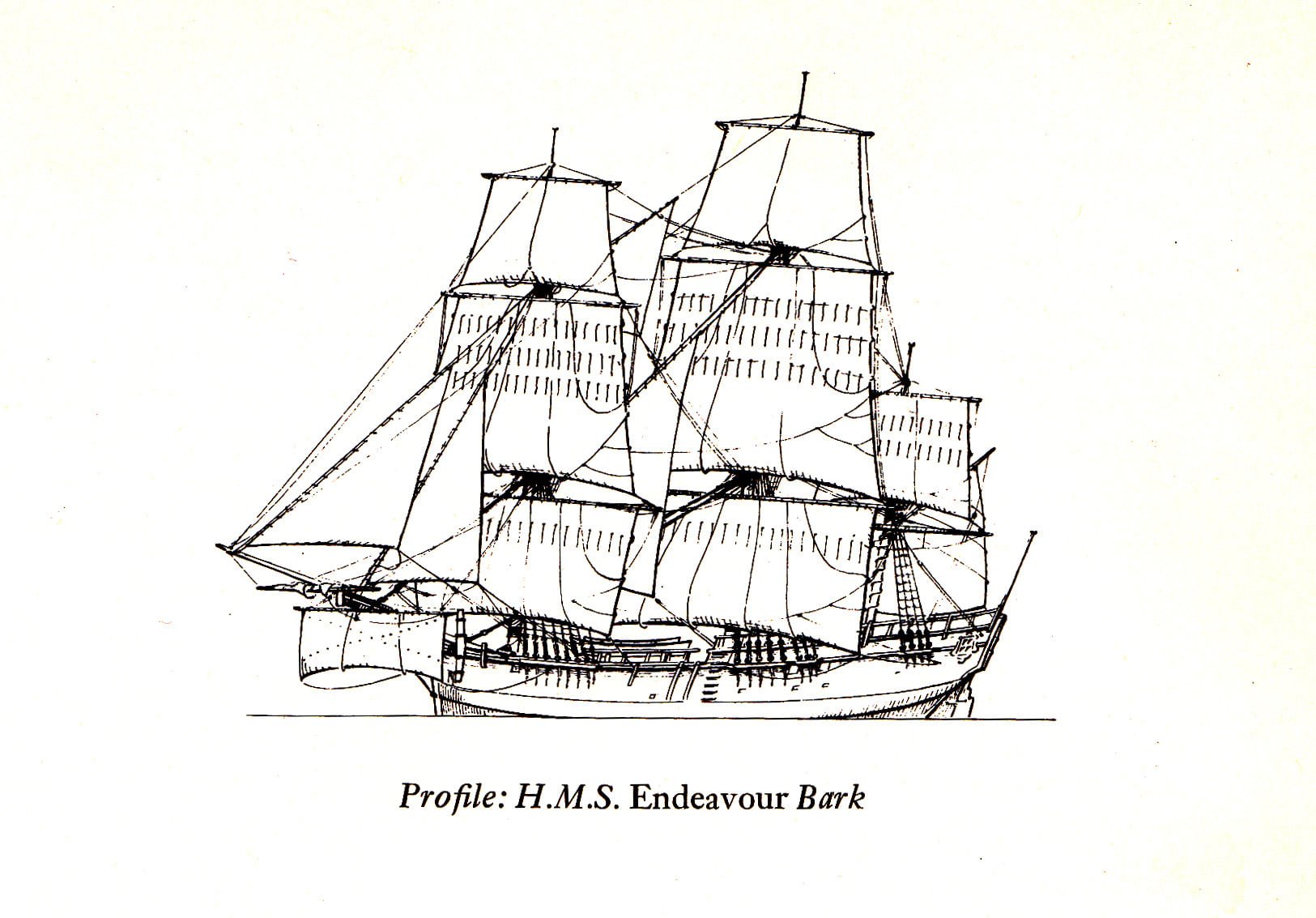

Tuesday, 14th. Winds at South-East, a steady gale. By 2 P.M. we got out to the outermost reefs, and just fetched to Windward of one of the openings I had discover'd from the Island; we tacked and Made a short trip to the South-West, while the Master went in the pinnace to examine the Channel, who soon made the signal for the Ship to follow, which we accordingly did, and in a short time got safe out. This Channel [now known as Cook's Passage] lies North-East 1/2 North, 3 Leagues from Lizard Island; it is about one-third of a Mile broad, and 25 or 30 fathoms deep or more. The moment we were without the breakers we had no ground with 100 fathoms of Line, and found a large Sea rowling in from the South-East. By this I was well assured we were got with out all the Shoals, which gave us no small joy, after having been intangled among Islands and Shoals, more or less, ever since the 26th of May, in which time we have sail'd above 360 Leagues by the Lead without ever having a Leadsman out of the Chains, when the ship was under sail; a Circumstance that perhaps never hapned to any ship before, and yet it was here absolutely necessary. I should have been very happy to have had it in my power to have keept in with the land, in order to have explor'd the Coast to the Northern extremity of the Country, which I think we were not far off, for I firmly believe this land doth not join to New Guinea. But this I hope soon either to prove or disprove, and the reasons I have before assign'd will, I presume, be thought sufficient for my leaving the Coast at this time; not but what I intend to get in with it again as soon as I can do it with safety. The passage or channel we now came out by, which I have named, —— [blank in MS] lies in the Latitude of 14 degrees 32 minutes South; it may always be found and known by the 3 high Islands within it, which I have called the Islands of Direction, because by their means a safe passage may be found even by strangers in within the Main reef, and quite into the Main. Lizard Island, which is the Northermost and Largest of the 3, Affords snug Anchorage under the North-West side of it, fresh water and wood for fuel; and the low Islands and Reefs which lay between it and the Main, abound with Turtle and other fish, which may be caught at all Seasons of the Year (except in such blowing weather as we have lately had). All these things considered there is, perhaps, not a better place on the whole Coast for a Ship to refresh at than this Island. I had forgot to mention in its proper place, that not only on this Island, but on Eagle Island, and on several places of the Sea beach in and about Endeavour River, we found Bamboos, Cocoa Nutts, the seeds of some few other plants, and Pummice-stones, which were not the produce of the Country. From what we have seen of it, it is reasonable to suppose that they are the produce of some lands or Islands laying in the Neighbourhood, most likely to the Eastward, and are brought hither by the Easterly trade winds. The Islands discover'd by Quiros lies in this parrallel, but how far to the Eastward it's hard to say; for altho' we found in most Charts his discoveries placed as far to the West as this country yet from the account of his Voyage, compared with what we ourselves have seen, we are Morally certain that he never was upon any part of this Coast. [The Island of Espiritu Santo, in the New Hebrides, which Quiros discovered, lies 1200 miles to the eastward, and New Caledonia, from which these objects might equally have come, is 1000 miles in the same direction.] As soon as we had got without the Reefs we Shortened sail, and hoisted in the pinnace and Long boat, which last we had hung alongside, and then stretched off East-North-East, close upon a wind, as I did not care to stand to the Northward until we had a whole day before us, for which reason we kept making short boards all night. The large hollow sea we have now got into acquaints us with a Circumstance we did not before know, which is that the Ship hath received more Damage than we were aware of, or could perceive when in smooth Water; for now she makes as much water as one pump will free, kept constantly at work. However this was looked upon as trifling to the Danger we had lately made an Escape from. At day light in the morning Lizard Island bore South by West, distant 10 Leagues. We now made all the sail we could, and stood away North-North-West 1/2 West, but at 9 we steer'd North-West 1/2 North, having the advantage of a Fresh Gale at South-East; at Noon we were by observation in the Latitude of 13 degrees 46 minutes South, the Lizard Island bore South 15 degrees East, distant 58 Miles, but we had no land in sight.

Banks’ Journal

14. For the first time these three months we were this day out of sight of Land to our no small satisfaction: that very Ocean which had formerly been look'd upon with terror by (maybe) all of us was now the Assylum we had long wishd for and at last found. Satisfaction was clearly painted in every mans face: the day was fine and the trade wind brisk before which we steerd to the Northward; the well grown waves which followd the ship, sure sign of no land being in our neighbourhood, were contemplated with the greatest satisfaction, notwithstanding we plainly felt the effect of the blows they gave to our crazy ship, increasing her leaks considerably so that she made now 9 inches water every hour. This however was lookd upon as a light evil in comparison to those we had so lately made our escape from.

August 15, 1770

Wednesday, 15th. Fresh Trade at South-East and Clear weather. At 6 in the evening shortned sail and brought too, with her head to the North-East. By this time we had run near 12 Leagues upon a North-West 1/2 North Course since Noon. At 4 a.m. wore and lay her head to the South-West, and at 6 made all Sail, and steer'd West, in order to make the land, being fearful of over shooting the passage, supposing there to be one, between this land and New Guinea. By noon we had run 10 Leagues upon this Course, but saw no land. Our Latitude by observation was 13 degrees 2 minutes South, Longitude 216 degrees 00 minutes West, which was 1 degree 23 minutes to the West of Lizard Island.

Banks’ Journal

15. Fine weather and moderate trade. The Captn fearfull of going too far from the Land, least he should miss an opportunity of examining whether or not the passage which is layd down in some charts between New Holland and New Guinea realy existed or not, steerd the ship west right in for the land; about 12 O'Clock it was seen from the Mast head and about one the Reef laying without it in just the same manner as when we left it. He stood on however resolving to stand off at night after having taken a nearer view, but just at night fall found himself in a manner embayd in the reef so that it was a moot Point whether or not he could weather it on either tack; we stood however to the Northward and at dark it was concluded that she would go clear of every thing we could see. The night however was not the most agreable: all the dangers we had escapd were little in comparison of being thrown upon this reef if that should be our lot. A Reef such a one as I now speak of is a thing scarcely known in Europe or indeed any where but in these seas: it is a wall of Coral rock rising almost perpendicularly out of the unfathomable ocean, always overflown at high water commonly 7 or 8 feet, and generaly bare at low water; the large waves of the vast ocean meeting with so sudden a resistance make here a most terrible surf Breaking mountain high, especialy when as in our case the general trade wind blows directly upon it.

August 16, 1770

Ship in Danger, Outside Barrier Reef

Thursday, 16th. Moderate breezes at East-South-East and fair weather. A little after Noon saw the Land from the Mast head bearing West-South-West, making high; at 2 saw more land to the North-West of the former, making in hills like Islands; but we took it to be a Continuation of the Main land. An hour after this we saw a reef, between us and the land, extending away to the Southward, and, as we thought, terminated here to the Northward abreast of us; but this was only on op'ning, for soon after we saw it extend away to the Northward as far as we could distinguish anything. Upon this we hauld close upon a Wind, which was now at East-South-East, with all the sail we could set. We had hardly trimm'd our sails before the wind came to East by North, which made our weathering the Reef very doubtful, the Northern point of which in sight at sun set still bore from us North by West, distant about 2 Leagues. However, this being the best Tack to Clear it, we keept standing to the Northward, keeping a good look out until 12 at night, when, fearing to run too far upon one Course, we tack'd and stood to the southward, having run 6 Leagues North or North by East since sun set; we had not stood above 2 Miles to the South-South-East before it fell quite Calm. We both sounded now and several times before, but had not bottom with 140 fathoms of line.

[The description which follows, of the situation of the ship, and the occurrences until she was safely anchored inside the Barrier Reef, is from the Admiralty copy, as it is much fuller than that in Mr. Corner's.] A little after 4 o'clock the roaring of the surf was plainly heard, and at daybreak the Vast foaming breakers were too plainly to be seen not a mile from us, towards which we found the ship was carried by the Waves surprisingly fast. We had at this time not an air of Wind, and the depth of water was unfathomable, so that there was not a possibility of anchoring. In this distressed Situation we had nothing but Providence and the small Assistance the Boats could give us to trust to; the Pinnace was under repair, and could not immediately be hoisted out. The Yawl was put in the Water, and the Longboat hoisted out, and both sent ahead to tow, which, together with the help of our sweeps abaft, got the Ship's head round to the Northward, which seemed to be the best way to keep her off the Reef, or at least to delay time. Before this was effected it was 6 o'clock, and we were not above 80 or 100 yards from the breakers. The same sea that washed the side of the ship rose in a breaker prodidgiously high the very next time it did rise, so that between us and destruction was only a dismal Valley, the breadth of one wave, and even now no ground could be felt with 120 fathom. The Pinnace was by this time patched up, and hoisted out and sent ahead to Tow. Still we had hardly any hopes of saving the ship, and full as little our lives, as we were full 10 Leagues from the nearest Land, and the boats not sufficient to carry the whole of us; yet in this Truly Terrible Situation not one man ceased to do his utmost, and that with as much Calmness as if no danger had been near. All the dangers we had escaped were little in comparison of being thrown upon this reef, where the Ship must be dashed to pieces in a Moment. A reef such as one speaks of here is Scarcely known in Europe. It is a Wall of Coral Rock rising almost perpendicular out of the unfathomable Ocean, always overflown at high Water generally 7 or 8 feet, and dry in places at Low Water. The Large Waves of the Vast Ocean meeting with so sudden a resistance makes a most Terrible Surf, breaking Mountains high, especially as in our case, when the General Trade Wind blows directly upon it. At this Critical juncture, when all our endeavours seemed too little, a Small Air of Wind sprung up, but so small that at any other Time in a Calm we should not have observed it. With this, and the Assistance of our Boats, we could observe the Ship to move off from the Reef in a slanting direction; but in less than 10 Minutes we had as flat a Calm as ever, when our fears were again renewed, for as yet we were not above 200 Yards from the Breakers. Soon after our friendly Breeze visited us again, and lasted about as long as before. A Small Opening was now Seen in the Reef about a 1/4 of a Mile from us, which I sent one of the Mates to Examine. Its breadth was not more than the Length of the Ship, but within was Smooth Water. Into this place it was resolved to Push her if Possible, having no other Probable Views to save her, for we were still in the very Jaws of distruction, and it was a doubt wether or no we could reach this Opening. However, we soon got off it, when to our Surprise we found the Tide of Ebb gushing out like a Mill Stream, so that it was impossible to get in. We however took all the Advantage Possible of it, and it Carried us out about a 1/4 of a Mile from the breakers; but it was too Narrow for us to keep in long. However, what with the help of this Ebb, and our Boats, we by Noon had got an Offing of 1 1/2 or 2 Miles, yet we could hardly flatter ourselves with hopes of getting Clear, even if a breeze should Spring up, as we were by this time embay'd by the Reef, and the Ship, in Spite of our Endeavours, driving before the Sea into the bight. The Ebb had been in our favour, and we had reason to Suppose the flood which was now made would be against us. The only hopes we had was another Opening we saw about a Mile to the Westward of us, which I sent Lieutenant Hicks in the Small Boat to Examine. Latitude observed 12 degrees 37 minutes South, the Main Land in Sight distant about 10 Leagues.

Banks’ Journal

16. At three O'Clock this morn it dropd calm on a sudden which did not at all better our situation: we judgd ourselves not more than 4 or 5 l'gs from the reef, maybe much less, and the swell of the sea which drove right in upon it carried the ship towards it fast. We tried the lead often in hopes to find ground that we might anchor but in vain; before 5 the roaring of the Surf was plainly heard and as day broke the vast foaming billows were plainly enough to be seen scarce a mile from us and towards which we found the ship carried by the waves surprizingly fast, so that by 6 o'clock we were within a Cables lengh of them, driving on as fast as ever and still no ground with 100 fathm of line. Every method had been taken since we first saw our danger to get the boats out in hopes that they might tow us off but it was not yet acomplishd; the Pinnace had had a Plank strippd off her for repair and the longboat under the Booms was lashd and fastned so well from our supposd security that she was not yet got out. Two large Oars or sweeps were got out at the stern ports to pull the ships head round the other way in hopes that might delay till the boats were out. All this while we were approaching and came I beleive before this could be effected within 40 yards of the breaker; the same sea that washd the side of the ship rose in a breaker enormously high the very next time is did rise, so between us and it was only a dismal valley the breadth of one wave; even now the lead was hove 3 or 4 lines fastned together but no ground could be felt with above 150 fathm. Now was our case truly desperate, no man I beleive but who gave himself intirely over, a speedy death was all we had to hope for and that from the vastness of the Breakers which must quickly dash the ship all to peices was scarce to be doubted. Other hopes we had none: the boats were in the ship and must be dashd in peices with her and the nearest dry land was 8 or 10 Leagues distant. We did not however cease our endeavours to get out the long boat which was by this time almost accomplishd. At this critical juncture, at this I must say terrible moment, when all asistance seemd too little to save even our miserable lives, a small air of wind sprang up, so small that at any other time in a calm we should not have observd it. We however plainly saw that it instantly checkd our progress; every sail was therefore put in a proper direction to catch it and we just obse[r]vd the ship to move in a slaunting direction off from the breakers. This at least gave us time and redoubling our efforts we at last got out the long boat and manning her sent her a head. The ship still movd a little off but in less than 10 minutes our little Breeze died away into as flat a calm as ever. Now was our anziety again renewd: innumerable small peices of paper &c were thrown over the ships side to find whither the boats realy movd her ahead or not and so little did she move that it remaind almost every other time a matter of dispute. Our little freindly Breeze now visited us again and lasted about as long as before, thrusting us possibly 100 yards farther from the breakers: we were still however in the very jaws of destruction. A small opening had been seen in the reef about a furlong from us, its breadth was scarce the lengh of the ship, into this however it was resolvd to push her if posible. Within was no surf, therefore we might save our lives: the doubt was only whether we could get the ship so far: our little breeze however a third time visited us and pushd us almost there. The fear of Death is Bitter: the prospect we now had before us of saving our lives tho at the expence of every thing we had made my heart set much lighter on its throne, and I suppose there were none but what felt the same sensations. At lengh we arrivd off the mouth of the wishd for opening and found to our surprize what had with the little breeze been the real cause of our Escape, a thing that we had not before dreamt of. The tide of flood it was that had hurried us so unacountably fast towards the reef, in the near neighbourhood of which we arrivd just at high water, consequently its ceasing to drive us any farther gave us the opportunity we had of getting off. Now however the tide of Ebb made strong and gushd out of our little opening like a mill stream, so that it was impossible to get in; of this stream however we took the advantage as much as possible and it Carried us out near a quarter of a mile from the reef. We well knew that we were to take all the advantage possible of the Ebb so continued towing with all our might and with all our boats, the Pinnance being now repaird, till we had gott an offing of 1_ or 2 miles. By this time the tide began to turn and our suspence began again: as we had gaind so little while the ebb was in our favour we had some reason to imagine that the flood would hurry us back upon the reef in spite of our utmost endeavours. It was still as calm as ever so no likely hood of any wind today; indeed had wind sprung up we could only have searchd for another opening, for we were so embayd by the reef that with the general trade wind it was impossible to get out. Another opning was however seen ahead and the 1st Lieutenant went away in the small boat to examine it. In the mean time we strugled hard with the flood, sometimes gaining a little then holding only our own and at others loosing a little, so that our situation was almost as bad as ever, as the flood had not yet come to its strengh. At 2 however the Lieutentant arrivd with news that the opening was very narrow: in it was good anchorage and a passage quite in free from shoals. The ships head was immediately put towards it and with the tide she towd fast so that by three we enterd and were hurried in by a stream almost like a mill race, which kept us from even a fear of the sides tho it was not above _ of mile in breadth. By 4 we came to an anchor happy once more to encounter those shoals which but two days before we thought ourselves supreamly happy to have escap'd from. How little do men know what is for their real advantage: two days [ago?] our utmost wishes were crownd by getting without the reef and today we were made again happy by getting within it.

August 17, 1770

Pass Again Inside Barrier Reef.

Tubipora musica – organ pipe coral

Friday, 17th. While Mr. Hicks was Examining the opening we struggled hard with the flood, sometime gaining a little and at other times loosing. At 2 o'Clock Mr. Hicks returned with a favourable Account of the Opening. It was immediately resolved to Try to secure the Ship in it. Narrow and dangerous as it was, it seemed to be the only means we had of saving her, as well as ourselves. A light breeze soon after sprung up at East-North-East, with which, the help of our Boats, and a Flood Tide, we soon entered the Opening, and was hurried thro' in a short time by a Rappid Tide like a Mill race, which kept us from driving against either side, though the Channel was not more than a 1/4 of a Mile broad, having 2 Boats ahead of us sounding.

[This picture of the narrow escape from total shipwreck is very graphic. Many a ship has been lost under similar circumstances, without any idea of anchoring, which would often save a vessel, as it is not often that a reef is so absolutely steep; but that Cook had this possibility in his mind is clear. As a proof of the calmness which prevailed on board, it may be mentioned that when in the height of the danger, Mr. Green, Mr. Clerke, and Mr. Forwood the gunner, were engaged in taking a Lunar, to obtain the longitude. The note in Mr. Green's log is: "These observations were very good, the limbs of sun and moon very distinct, and a good horizon. We were about 100 yards from the reef, where we expected the ship to strike every minute, it being calm, no soundings, and the swell heaving us right on.]

Our deepth of water was from 30 to 7 fathoms; very irregular soundings and foul ground until we had got quite within the Reef, where we Anchor'd in 19 fathoms, a Coral and Shelly bottom. The Channel we came in by, which I have named Providential Channell, bore East-North-East, distant 10 or 12 Miles, being about 8 or 9 Leagues from the Main land, which extended from North 66 degrees West to South-West by South.

It is but a few days ago that I rejoiced at having got without the Reef; but that joy was nothing when Compared to what I now felt at being safe at an Anchor within it. Such are the Visissitudes attending this kind of Service, and must always attend an unknown Navigation where one steers wholy in the dark without any manner of Guide whatever. Was it not from the pleasure which Naturly results to a man from his being the first discoverer, even was it nothing more than Land or Shoals, this kind of Service would be insupportable, especially in far distant parts like this, Short of Provisions and almost every other necessary. People will hardly admit of an excuse for a Man leaving a Coast unexplored he has once discovered. If dangers are his excuse, he is then charged with Timerousness and want of Perseverance, and at once pronounced to be the most unfit man in the world to be employ'd as a discoverer; if, on the other hand, he boldly encounters all the dangers and Obstacles he meets with, and is unfortunate enough not to succeed, he is then Charged with Temerity, and, perhaps, want of Conduct. The former of these Aspersions, I am confident, can never be laid to my Charge, and if I am fortunate to Surmount all the Dangers we meet with, the latter will never be brought in Question; altho' I must own that I have engaged more among the Islands and Shoals upon this Coast than perhaps in prudence I ought to have done with a single Ship [Cook was so impressed with the danger of one ship alone being engaged in these explorations, that in his subsequent voyages he asked for, and obtained, two vessels.] and every other thing considered. But if I had not I should not have been able to give any better account of the one half of it than if I had never seen it; at best, I should not have been able to say whether it was Mainland or Islands; and as to its produce, that we should have been totally ignorant of as being inseparable with the other; and in this case it would have been far more satisfaction to me never to have discover'd it. But it is time I should have done with this Subject, which at best is but disagreeable, and which I was lead into on reflecting on our late Dangers.

In the P.M., as the wind would not permit us to sail out by the same Channel as we came in, neither did I care to move until the pinnace was in better repair, I sent the Master with all the other Boats to the Reef to get such refreshments as he could find, and in the meantime the Carpenters were repairing the pinnace. Variations by the Amplitude and Azimuth in the morning 4 degrees 9 minutes Easterly; at noon Latitude observed 12 degrees 38 minutes South, Longitude in 216 degrees 45 minutes West. It being now about low water, I and some other of the officers went to the Masthead to see what we could discover. Great part of the reef without us was dry, and we could see an Opening in it about two Leagues farther to the South-East than the one we came in by; we likewise saw 2 large spots of sand to the Southward within the Reef, but could see nothing to the Northward between it and the Main. On the Mainland within us was a pretty high promontary, which I called Cape Weymouth (Latitude 12 degrees 42 minutes South, Longitude 217 degrees 15 minutes); and on the North-West side of this Cape is a Bay, which I called Weymouth Bay. [Viscount Weymouth was one of the Secretaries of State when the Endeavour sailed.]

Banks’ Journal

17. As we were now safe at an anchor it was resolvd to send the boats upon the nearest shoal to search for shell fish, turtle or whatever else they could get. They accordingly went and Dr Solander and myself accompanied them in my small boat. In our way we met with two water snakes, one 5 the other 6 feet long; we took them both; they much resembled Land snakes only their tails were flatted sideways, I suppose for the convenience of swimming, and were not venomous. The shoal we went upon was the very reef we had so near been lost upon yesterday, now no longer terrible to us; it afforded little provision for the ship, no turtle, only 300lb of Great cockles, some were however of an immense size. We had in the way of curiosity much better success, meeting with many curious fish and mollusca besides Corals of many species, all alive, among which was the Tubipora musica. I have often lamented that we had not time to make proper observations upon this curious tribe of animals but we were so intirely taken up with the more conspicuous links of the chain of creation as fish, Plants, Birds &c &c. that it was impossible

August 18, 1770

Map from “Endeavour’”by Peter Aughton

Saturday, 18th. Gentle breezes at East and East-South-East. At 4 P.M. the Boats return'd from the Reef with about 240 pounds of Shell-fish, being the Meat of large Cockles, exclusive of the Shells. Some of these Cockles are as large as 2 Men can move, and contain about 20 pounds of Meat, very good. At 6 in the morning we got under sail, and stood away to the North-West, as we could not expect a wind to get out to Sea by the same Channel as we came in without waiting perhaps a long time for it, nor was it advisable at this time to go without the Shoals, least we should by them be carried so far off the Coast as not to be able to determine wether or no New Guinea joins to or makes a part of this land. This doubtful point I had from my first coming upon the Coast, determined, if Possible, to clear up; I now came to a fix'd resolution to keep the Main land on board, let the Consequence be what it will, and in this all the Officers concur'd. In standing to the North-West we met with very irregular soundings, from 10 to 27 fathoms, varying 5 or 6 fathoms almost every Cast of the Lead. However, we keept on having a Boat ahead sounding.

A little before noon we passed a low, small, sandy Isle, which we left on our Starboard side at the distance of 2 Miles. At the same time we saw others, being part of large Shoals above water, away to the North-East and between us and the Main land. At Noon we were by observation in the Latitude of 12 degrees 28 minutes South, and 4 or 5 Leagues from the Main, which extended from South by West to North 71 degrees West, and some Small Islands extending from North 40 degrees West to North 54 degrees West, the Main or outer Reef seen from the Masthead away to the North-East.

Banks’ Journal

18. Weighd and stood along shore with a gentle breeze, the main still 7 or 8 Leagues from us. In the even many shoals were ahead; we were however fortunate enough to find our way through them and at night anchord under an Island. The tide here ran immensely strong which we lookd upon as a good omen: so strong a stream must in all probability have an outlet by which we could get out either on the South or North side of New Guinea. The smoothness of the water however plainly indicated that the reef continued between us and the Ocean.

August 19 1770

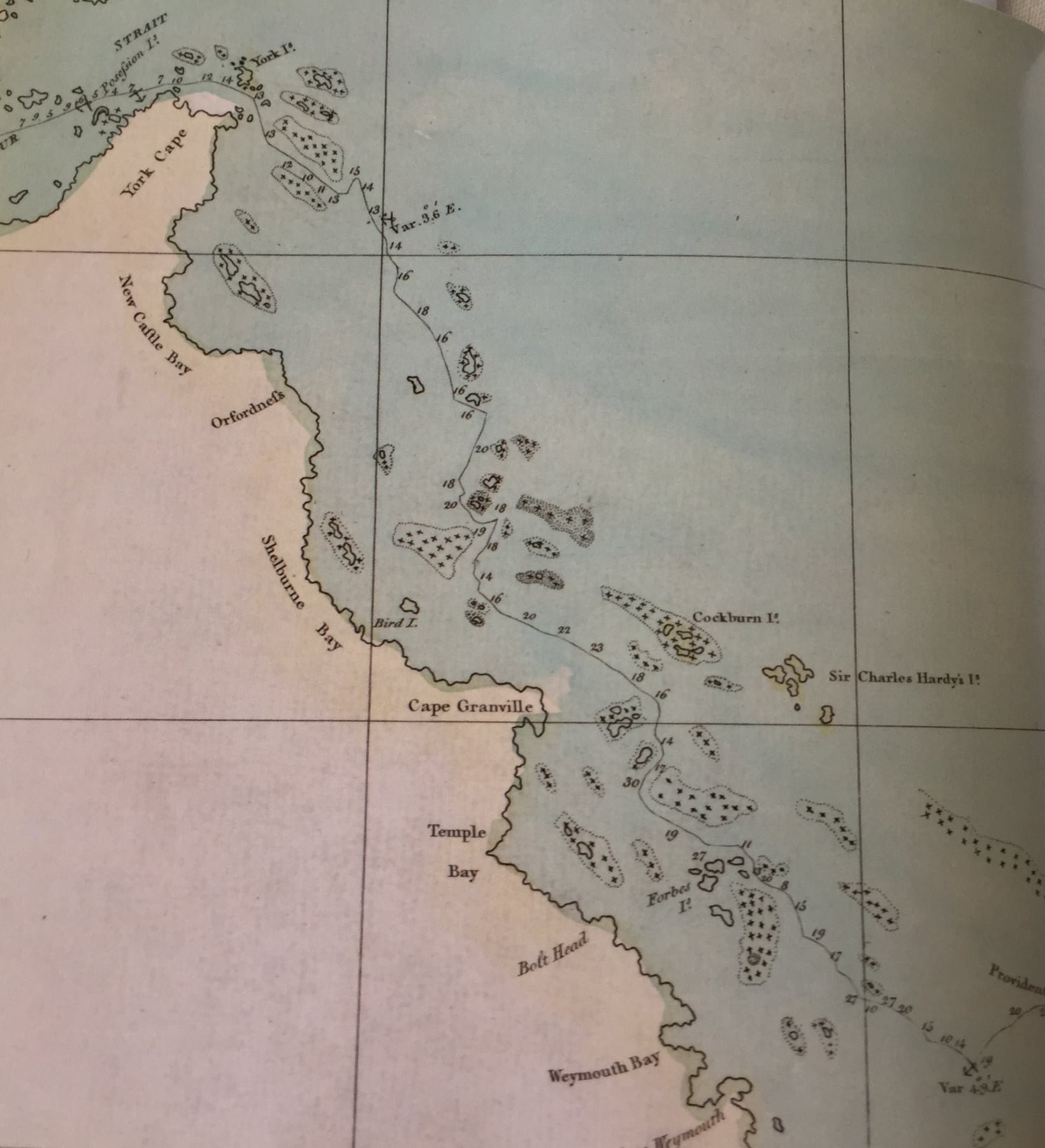

Amongst the shoals off Cape Grenville

Sunday, 19th. Gentle breezes at South-East by East and Clear wether. At 2 P.M., as we were steering North-West by North, saw a large shoal right ahead, extending 3 or 4 points on each bow, upon which we hauld up North-North-East and North-East by North, in order to get round to North Point of it, which we reached by 4 o'clock, and then Edged away to the westward, and run between the North end of this Shoal and another, which lays 2 miles to the Northward of it, having a Boat all the time ahead sounding. Our depth of Water was very irregular, from 22 to 8 fathoms. At 1/2 past 6 we Anchor'd in 13 fathoms; the Northermost of the Small Islands mentioned at Noon bore West 1/2 South, distant 3 Miles. These Islands, which are known in the Chart by the name of Forbes's Isles, [Admiral John Forbes was a Commissioner of Longitude in 1768, and had been a Lord of the Admiralty from 1756 to 1763] lay about 5 Leagues from the Main, which here forms a moderate high point, which we called Bolt head, from which the Land trends more westerly, and is all low, sandy Land, but to the Southward it is high and hilly, even near the Sea.

At 6 A.M. we got under sail, and directed our Course for an Island which lay but a little way from the Main, and bore from us at this time North 40 degrees West, distant 5 Leagues; but we were soon interrupted in our Course by meeting with Shoals, but by the help of 2 Boats ahead and a good lookout at the Mast head we got at last into a fair Channel, which lead us down to the Island, having a very large Shoal on our Starboard side and several smaller ones betwixt us and the Main land. In this Channel we had from 20 to 30 fathoms. Between 11 and 12 o'Clock we hauld round the North-East side of the Island, leaving it between us and the Main from which it is distant 7 or 8 Miles. This Island is about a League in Circuit and of a moderate height, and is inhabited; to the North-West of it are several small, low Islands and Keys, which lay not far from the Main, and to the Northward and Eastward lay several other Islands and Shoals, so that we were now incompassed on every side by one or the other, but so much does a great danger Swallow up lesser ones, that these once so much dreaded spots were now looked at with less concern. The Boats being out of their Stations, we brought too to wait for them. At Noon our Latitude by observation was 12 degrees 0 minutes South, Longitude in 217 degrees 25 minutes West; depth of Water 14 fathoms; Course and distance sail'd, reduced to a strait line, since yesterday Noon is North 29 degrees West, 32 Miles.

The Main land within the above Islands forms a point, which I call Cape Grenville [George Grenville was First Lord of the Admiralty for a few months in 1763, and afterwards Prime Minister for two years] (Latitude 11 degrees 58 minutes, Longitude 217 degrees 38 minutes); between this Cape and the Bolt head is a Bay, which I Named Temple Bay. [Richard Earl Temple, brother of George Grenville, was First Lord of the Admiralty in 1756] East 1/2 North, 9 Leagues from Cape Grenville, lay some tolerable high Islands, which I called Sir Charles Hardy's Isles; [Admiral Sir C. Hardy was second in command in Hawke's great action in Quiberon Bay, 1759] those which lay off the Cape I named Cockburn Isles. [Admiral George Cockburn was a Commissioner of Longitude and Comptroller of the Navy when Cook left England. Off Cape Grenville the Endeavour again got into what is now the recognised channel along the land inside the reefs]

Banks’ Journal

19. Weighd anchor and steerd as yesterday with a fresh trade wind. All morn were much entangled with Shoals, but so much do great dangers swallow up lesser ones that these once so much dreaded shoals were now look[ed] at with much less concern than formerly. At noon we passd along a large shoal on which the boats which were ahead saw many turtle but it blew to[o] fresh to catch them. We were now tolerably near the main, which appeard low and barren and often interspersd with large patches of the very white sand spoke of before. On a small Island which we passd very near to were 5 natives, 2 of whoom carried their Lances in their hands; they came down upon a point and lookd at the ship for a little while and then retird.

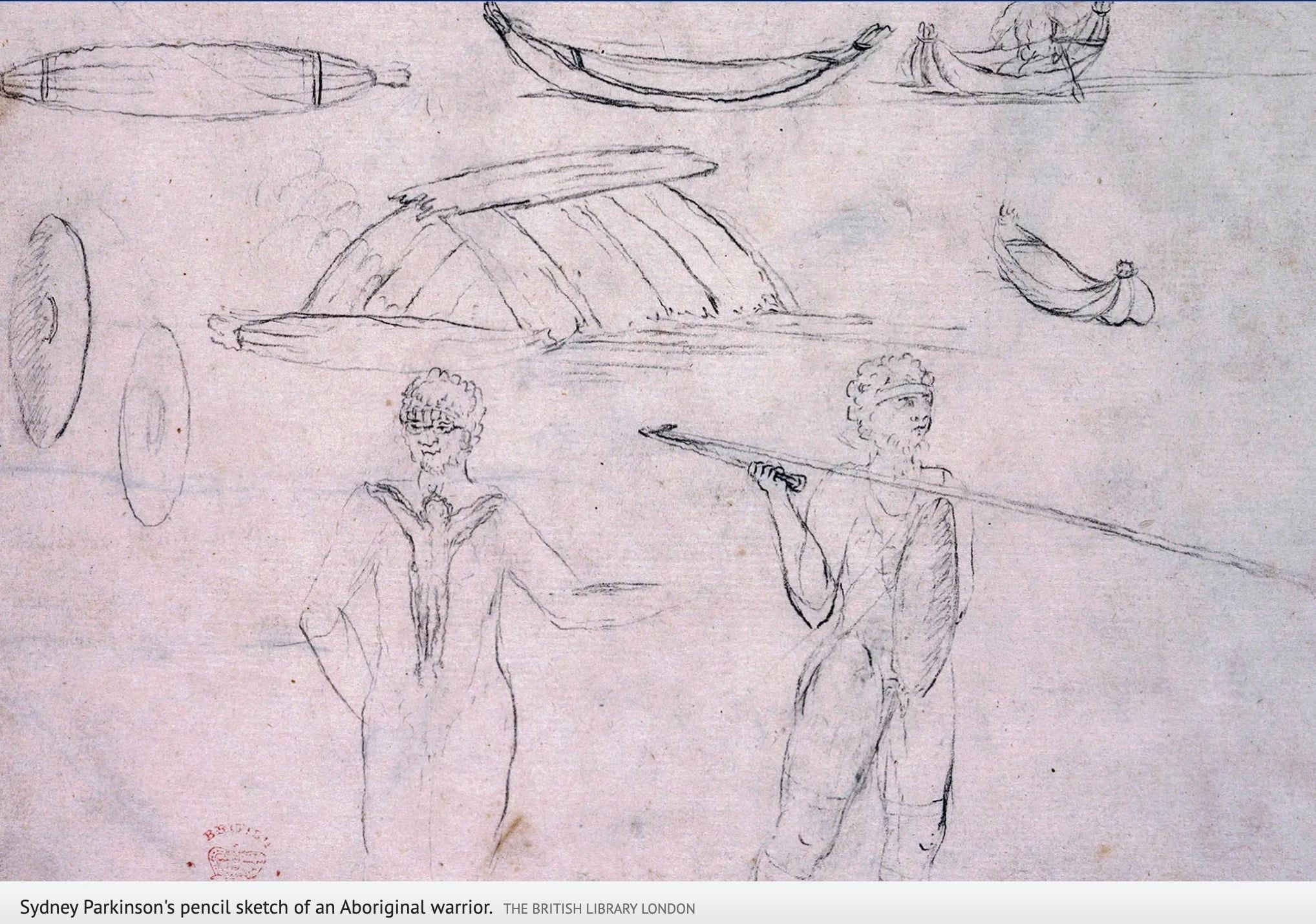

Sketch of aboriginals by Sydney Parkinson

Painting of George Grenville by ???

August 20, 1770

Nearing Cape York, Queensland

Monday, 20th. Fresh breezes at East-South-East. About one P.M. the pinnace having got ahead, and the Yawl we took in Tow, we fill'd and Steer'd North by West, for some small Islands we had in that direction. After approaching them a little nearer we found them join'd or connected together by a large Reef; upon this we Edged away North-West, and left them on our Starboard hand, steering between them and the Island laying off the Main, having a fair and Clear Passage; Depth of Water from 15 to 23 fathoms. At 4 we discover'd some low Islands and Rocks bearing West-North-West, which we stood directly for. At half Past 6 we Anchor'd on the North-East side of the Northermost, in 16 fathoms, distant from the Island one Mile. This Isle lay North-West 4 Leagues from Cape Grenville. On the Isles we saw a good many Birds, which occasioned my calling them Bird Isles. Before and at Sunset we could see the Main land, which appear'd all very low and sandy, Extends as far to the Northward as North-West by North, and some Shoals, Keys, and low sandy Isles away to the North-East of us.

At 6 A.M. we got again under sail, with a fresh breeze at East, and stood away North-North-West for some low Islands [Boydong Keys] we saw in that direction; but we had not stood long upon this Course before we were obliged to haul close upon a wind in Order to weather a Shoal which we discover'd on our Larboard bow, having at the same time others to the Eastward of us. By such time as we had weathered the Shoal to Leeward we had brought the Islands well upon our Leebow; but seeing some Shoals spit off from them, and some rocks on our Starboard bow, which we did not discover until we were very near them, made me afraid to go to windward of the Islands; wherefore we brought too, and made the signal for the pinnace, which was a head, to come on board, which done, I sent her to Leeward of the Islands, with Orders to keep along the Edge off the Shoal, which spitted off from the South side of the Southermost Island. The Yawl I sent to run over the Shoals to look for Turtle, and appointed them a Signal to make in case they saw many; if not, she was to meet us on the other side of the Island. As soon as the pinnace had got a proper distance from us we wore, and stood After her, and run to Leeward of the Islands, where we took the Yawl in Tow, she having seen only one small Turtle, and therefore made no Stay upon the Shoal. Upon this Island, which is only a Small Spott of Land, with some Trees upon it, we saw many Hutts and habitations of the Natives, which we supposed come over from the Main to these Islands (from which they are distant about 5 Leagues) to Catch Turtle at the time these Animals come ashore to lay their Eggs. Having got the Yawl in Tow, we stood away after the pinnace North-North-East and North by East to 2 other low Islands, having 2 Shoals, which we could see without and one between us and the Main.

At Noon we were about 4 Leagues from the Main land, which we could see Extending to the Northward as far as North-West by North, all low, flat, and Sandy. Our Latitude by observation was 11 degrees 23 minutes South, Longitude in 217 degrees 46 minutes West, and Course and distance sail'd since Yesterday at Noon North 22 degrees West, 40 Miles; soundings from 14 to 23 fathoms. But these are best seen upon the Chart, as likewise the Islands, Shoals, etc., which are too Numerous to be Mentioned singly.

[It is very difficult to follow Cook's track after entering Providential Channel to this place. The shoals and islands were so confusing that their positions are very vaguely laid down on Cook's chart. It is easy to imagine how slow was his progress and tortuous his course, with a boat ahead all the time constantly signalling shallow water. Nothing is more trying to officers and men]

Banks’ Journal

20. Steering along shore as usual among many shoals, Luffing up for some and bearing away for others. We are now pretty well experiencd in their appearances so as seldom to be deceivd and easily to know asunder a bottom colourd by white sand from a coral rock, the former of which, tho generaly in 12 or 14 fathom water, some time ago gave us much trouble. The reef was still supposd to be without us from the smoothness of our water. The mainland appeard very low and sandy and had many fires upon it, more than we had usualy observd. We passd during the day many low sandy Islands every one of which stood upon a large shoal; we have constantly found the best passage to lie near the main, and the farther from that you go near the reef the more numerous are the shoals. In the evening we observd the shoals to decrease in number but we still were in smooth water.

Wikipedia

At sea, a league is three nautical miles (3.452 miles; 5.556 kilometres).

Cook’s Endeavour Journal NLA

On 20 August Cook reached the very end of New Holland. It had taken three months, nearly two of which had been spent on a beach but the Endeavour had sailed the entire length of the Great Barrier Reef. Cook would later name the perilous stretch of water between Cape Grafton near Cairns and Cape York, the Labyrinth “after having been entangled among the coral shoals more or less every sence (sic).”

August 21, 1770

The Duke of York, Edward August

Tuesday, 21st. Winds at East by South and East-South-East, fresh breeze. By one o'Clock we had run nearly the length of the Southermost of the 2 Islands before mentioned, and finding that we could not well go to windward of them without carrying us too far from the Main land, we bore up, and run to Leeward, where we found a fair open passage. This done, we steer'd North by West, in a parrallel direction with the Main land, leaving a small Island between us and it, and some low sandy Isles and Shoals without us, all of which we lost sight of by 4 o'Clock; neither did we see any more before the sun went down, at which time the farthest part of the Main in sight bore North-North-West 1/2 West. Soon after this we Anchor'd in 13 fathoms, soft Ground, about five Leagues from the Land, where we lay until day light, when we got again under sail, having first sent the Yawl ahead to sound. We steer'd North-North-West by Compass from the Northermost land in sight; Variation 3 degrees 6 minutes East. Seeing no danger in our way we took the Yawl in Tow, and made all the Sail we could until 8 o'Clock, at which time we discover'd Shoals ahead and on our Larboard bow, and saw that the Northermost land, which we had taken to be a part of the Main, was an Island, or Islands, [Now called Mount Adolphus Islands] between which and the Main their appeared to be a good Passage thro' which we might pass by running to Leeward of the Shoals on our Larboard bow, which was now pretty near us. Whereupon we wore and brought too, and sent away the Pinnace and Yawl to direct us clear of the Shoals, and then stood after them. Having got round the South-East point of the Shoal we steer'd North-West along the South-West, or inside of it, keeping a good lookout at the Masthead, having another Shoal on our Larboard side; but we found a good Channel of a Mile broad between them, wherein were from 10 to 14 fathoms. At 11 o'Clock, being nearly the length of the Islands above mentioned, and designing to pass between them and the Main, the Yawl, being thrown a stern by falling in upon a part of the Shoal, She could not get over. We brought the Ship too, and Sent away the Long boat (which we had a stern, and rigg'd) to keep in Shore upon our Larboard bow, and the Pinnace on our Starboard; for altho' there appear'd nothing in the Passage, yet I thought it necessary to take this method, because we had a strong flood, which carried us on end very fast, and it did not want much of high water. As soon as the Boats were ahead we stood after them, and got through by noon, at which time we were by observation in the Latitude of 10 degrees 36 minutes 30 seconds South.

The nearest part of the Main, and which we soon after found to be the Northermost, [Cape York, the northernmost point of Australia] bore West southerly, distant 3 or 4 Miles; the Islands which form'd the passage before mentioned extending from North to North 75 degrees East, distant 2 or 3 Miles. At the same time we saw Islands at a good distance off extending from North by West to West-North-West, and behind them another chain of high land, which we likewise judged to be Islands [The islands around Thursday Island] The Main land we thought extended as far as North 71 degrees West; but this we found to be Islands.