Over 250 years ago, Lieutenant James Cook sailed up our Queensland coast in his bark The HMB Endeavour.

It was the first of three long voyages that he commanded, and the aim of this one was to observe the transit of Venus across the sun on June 3 and 4 in 1769. This was best achieved in Tahiti, which he called George’s Land or King George’s Island after King George III of England.

He was also charged by the Royal Navy in London to explore Terra Australis Incognita or "undiscovered southern land", named by Abel Tasman in 1642 when he thought he saw an unknown continent on the southern horizon from his landfall in New Zealand.

It was generally believed that there must be some land in the south to ‘balance’ the land already discovered in the northern hemisphere. Sketchy maps had appeared between the 15th and 18th centuries.

In 1606 the Duyfken, a tiny Dutch ship visited the western shores of Cape York Peninsula, becoming the first European ship to make landfall on the Australian continent. During the 1600s more Dutch sightings of the continent led to the charting of the entire northern and western coastlines and much of the southern coast including part of Tasmania. The last expedition of the ships of the East India Company to northern Australia took place in 1756.

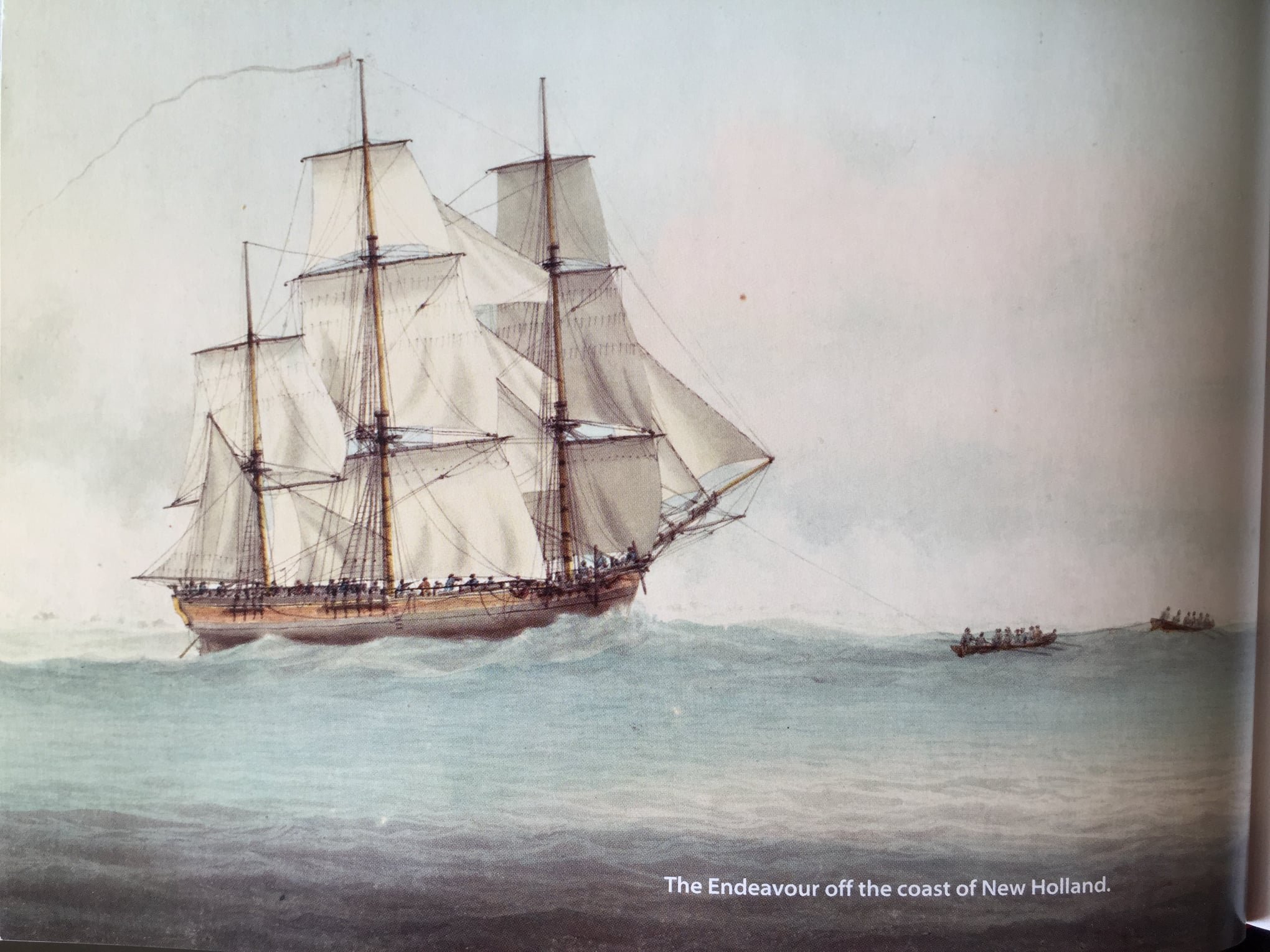

Painting of "The Endeavour" By Samuel Atkins c.1794 NLA

In 1606 Luis Vaez de Torres had sailed through a passage south of New Guinea but reports of the voyage had been hushed up.

Cook’s voyage took almost three years, departing from Plymouth Dockyard in England on 25 August 1768.

He travelled to Tahiti, then charted both islands of New Zealand before sighting the New Holland – later named Australia – shore at Point Hicks in Gippsland Victoria on 19 April 1770.

“All the dates that appear in Cook’s journal are ’ship time’. On land, a day is measured from one midnight to the next. Aboard ship it begins at noon and ends at noon 24 hours later. This explains why Cook’s pm comes before his am.” Quoted from the book ‘Cook’s Endeavour Journal – the inside story’ from the National Library of Australia.

He went on to anchor in Botany Bay in April 1770, which he named for all the specimens botanists that Joseph Banks and Dr Daniel Solander collected there.

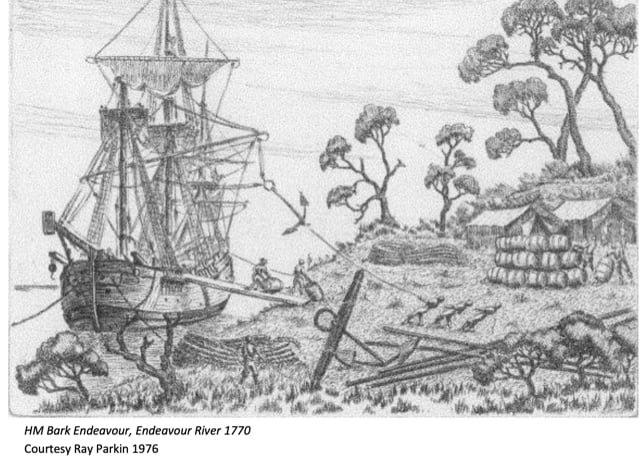

He sailed past the entrance to Sydney Harbour and hastened northward up the coast, anxious to arrive in Batavia, now Java, to replenish his supplies. The ship only landed a few times on New Holland’s shores to take on water, until spending almost two months at what is now Cooktown, to repair a large hole in the ship caused by hitting a coral reef.

Cook’s exceptional ability to map the eastern coast of Australia is still recognised today and the names he gave to many rivers, bays and promontories are still in use.

Source / ‘Cook’s Endeavour Journal’ by the National Library of Australia

June 2 1770

Off Cape Hillsborough, Queensland

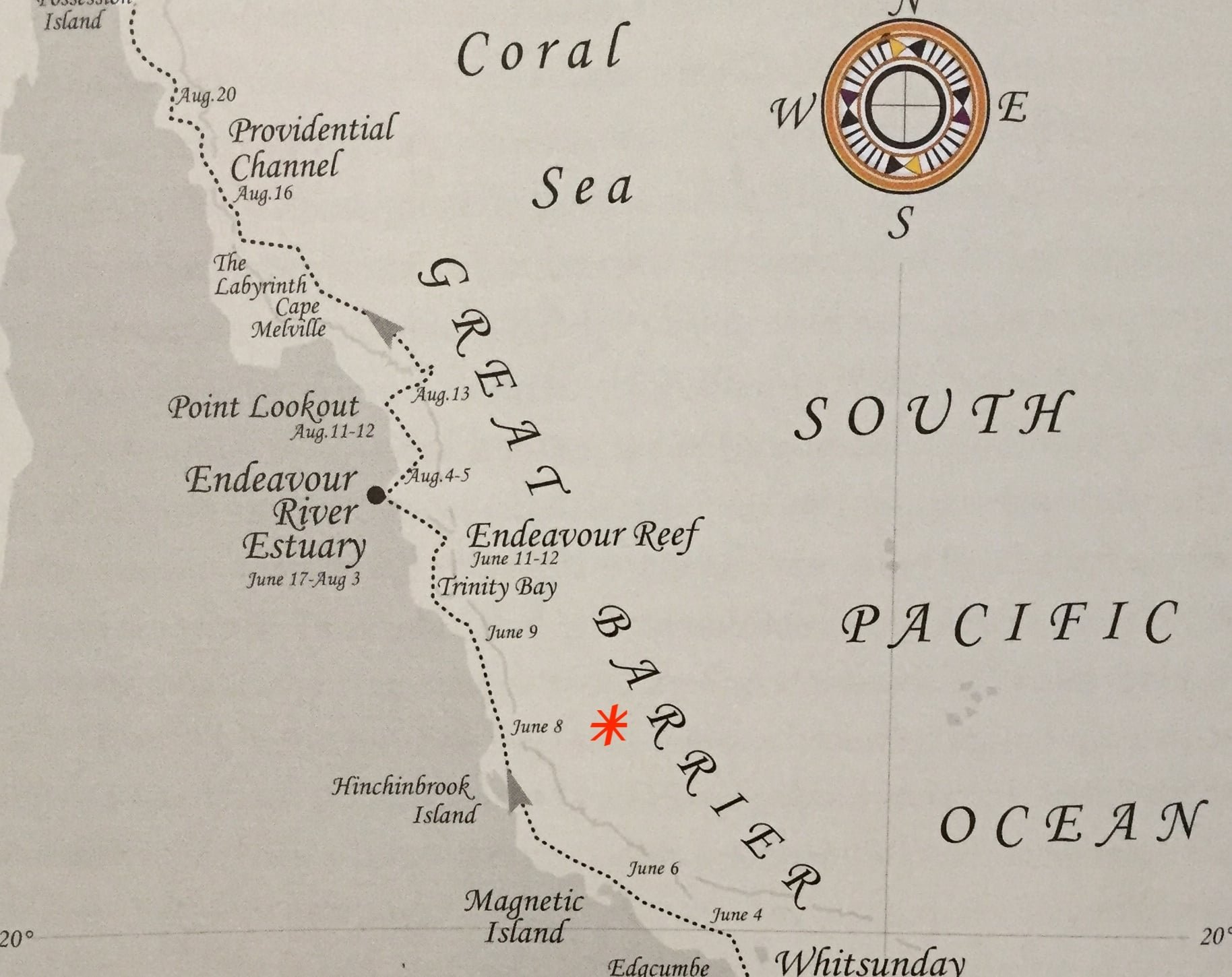

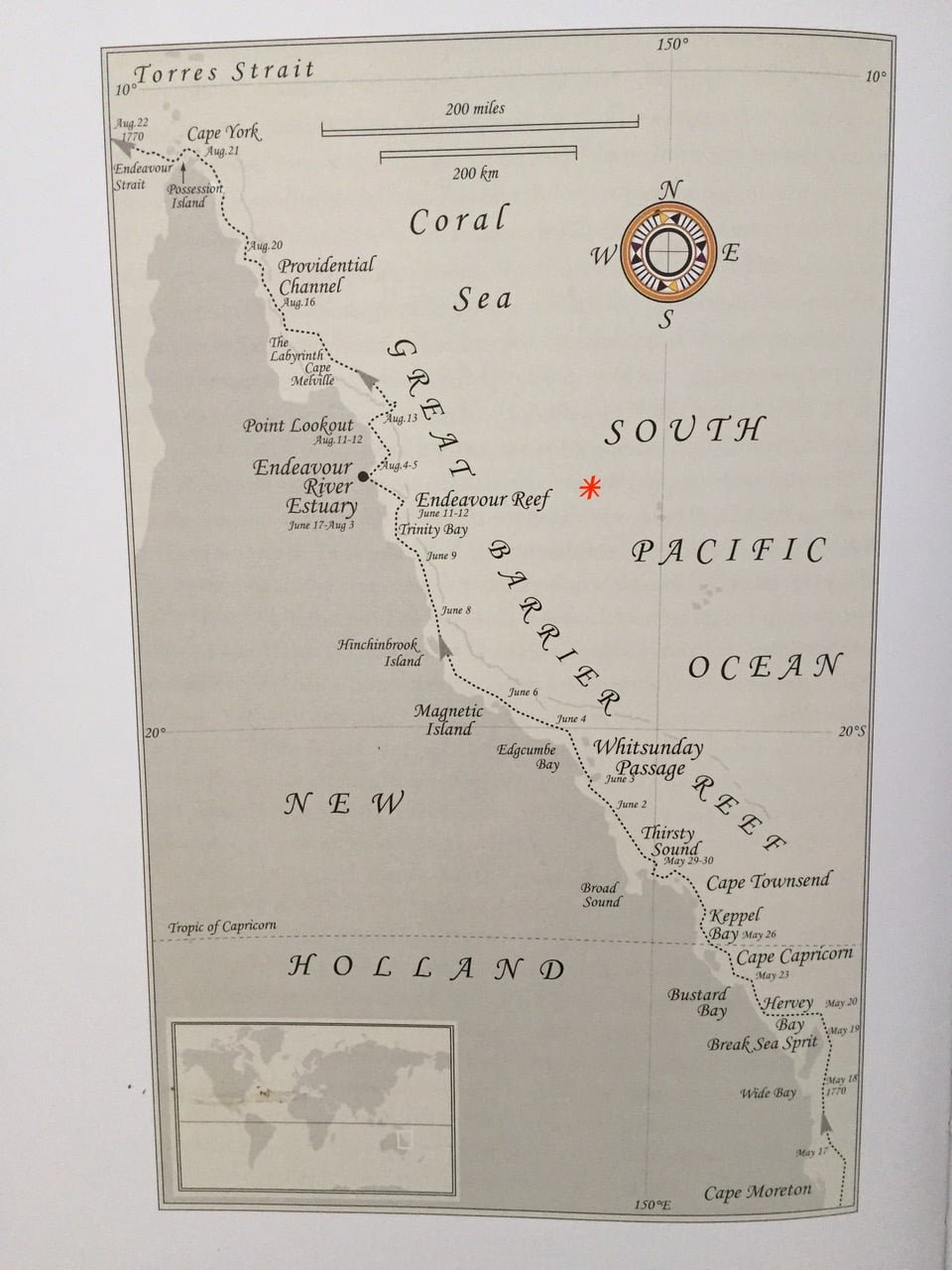

Map from "Endeavour” by Peter Aughton

Saturday, 2nd. Winds at South-South-East and South-East, a gentle breeze, with which we stood to the North-West and North-West by North, as the land lay, under an easey Sail. Having a boat ahead, found our Soundings at first were very irregular, from 9 to 4 fathoms; but afterwards regular, from 9 to 11 fathoms. At 8, being about 2 Leagues from the Main Land, we Anchor'd in 11 fathoms, Sandy bottom. Soon after this we found a Slow Motion of a Tide seting to the Eastward, and rode so until 6, at which time the tide had risen 11 feet; we now got under Sail, and Stood away North-North-West as the land lay. From the Observations made on the tide last Night it is plain that the flood comes from the North-West; whereas Yesterday and for Several days before we found it to come from the South-East. In steering along shore between the Island and the Main, at the Distance of 2 Leagues from the Latter, and 3 or 4 from the former, our soundings were Regular, from 12 to 9 fathoms; but about 11 o'Clock we were again embarrassed with Shoal Water [Blackwood Shoals], but got clear without letting go an Anchor; we had at one time not quite 3 fathoms. At Noon we were about 2 Leagues from the Main land, and about 4 from the Islands without us; our Latitude by Observation was 20 degrees 56 minutes South, Longitude made from Cape Palmerston 16 degrees West; a pretty high Promontory, which I named Cape Hillsborough, [The Earl of Hillsborough was the First Secretary of State for the Colonies, and President of the Board of Trade when the Endeavour sailed.] bore West 1/2 North, distant 7 Miles. The Main Land is here pretty much diversified with Mountains, Hills, plains, and Vallies, and seem'd to be tollerably Cloathed with Wood and Verdure. These Islands, which lay Parrallel with the Coast, and from 5 to 8 or 9 Leagues off, are of Various Extent, both for height and Circuit; hardly any Exceeds 5 Leagues in Circuit, and many again are very small. [The Cumberland Islands. They stretch along the coast for 60 miles.] Besides the Chain of Islands, which lay at a distance from the Coast, there are other Small Ones laying under the Land. Some few smokes were seen on the Main land.

On land a league is 3 miles. At sea a league is 3.45 miles or 5.5 kms

A fathom is a unit of length equal to six feet (1.8 metres), chiefly used in reference to the depth of water.

A shoal is a natural submerged ridge, a sandy elevation of the bottom of a body of water, constituting a hazard to navigation; a sandbank or sandbar.

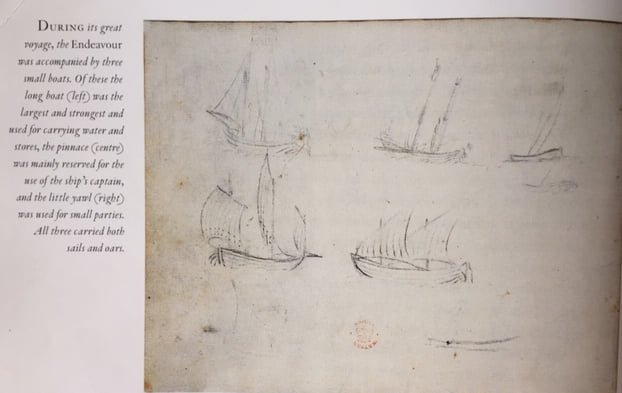

Three small boats accompanied the Endeavour. A pinnace, reserved for the use of the ship’s captain, a yawl, just large enough to carry four rowers and three passengers, and a long boat for carrying water and stores. All three had sails and oars and were stored on deck.

June 3 1770

Sunday, 3rd. Winds between the South by East and South-East. A Gentle breeze and Clear weather. In the P.M. we steer'd along shore North-West 1/2 West, at the distance of 2 Leagues from the Main, having 9 and 10 fathoms regular soundings. At sun set the furthest point of the Main Land that we could distinguish as such bore North 48 degrees West; to the Northward of this lay some high land, which I took to be an Island, the North West point of which bore North 41 degrees West; but as I was not sure that there was a passage this way, we at 8 came to an Anchor in 10 fathoms, muddy bottom. 2 hours after this we had a tide setting to the Northward, and at 2 o'clock it had fallen 9 Feet since the time we Anchored. After this the Tide began to rise, and the flood came from the Northward, which was from the Islands out at Sea, and plainly indicated that there was no passage to the North-West; but as this did not appear at day light when we got under Sail, and stood away to the North-West until 8, at this time we discover'd low land, quite a Cross what we took for an Opening between the Main and the Islands, which proved to be a Bay about 5 or 6 Leagues deep. We found the Main land trend away North by West 1/2 West, and a Strait or Passage between it and a Large Island [Whitsunday Island] or Islands laying in a Parrallel direction with the Coast; this passage we Stood into, having the Tide of Ebb in our favour. At Noon we were just within the Entrance, and by observation in the Latitude of 20 degrees 26 minutes South; Cape Hillsborough bore South by East, distant 10 Leagues, and the North point of the Bay before mentioned bore South 19 degrees West, distance 4 Miles. This point I have named Cape Conway [General H.S. Conway was Secretary of State 1765 to 1768] (Latitude 20 degrees 30 minutes, Longitude 211 degrees 28 minutes), and the bay, Repulse Bay, which is formed by these 2 Capes. The greatest and least depth of Water we found in it was 13 and 8 fathoms; every where safe Anchoring, and I believe, was it properly examined, there would be found some good Harbour in it, especially on the North Side within Cape Conway, for just within the Cape lay 2 or 3 Small Islands, which alone would shelter that side of the Bay from the South-East and Southerly winds, which seem to be the prevailing or Trade Winds. Among the many islands that lay upon this Coast there is one more remarkable than the rest, [Probably Blacksmith Island] being of a Small circuit, very high and peaked, and lies East by South, 10 Miles from Cape Conway at the South end of the Passage above mention'd.

From the Journal of botanist Joseph Banks

3. At day break the anchor was weighd and we stood along shore till we found ourselves in a bay off the outermost point of which were the Islands seen yesterday; by 8 it was resolvd to stand out again through a passage which was seen between them and the main which was accordingly done. The countrey within the bay, especialy on the innermost side, was well wooded, lookd fertile and pleasant. After dinner standing among Islands which were very barren, rising high and steep from the sea; on one of these we saw with our glasses 2 men a woman and a small canoe fitted with an outrigger, which made us hope that the people were something improvd as their boat was far preferable to the bark Canoes of Stingrays bay.

Stingrays Bay was later named Botany Bay by Lieut Cook.

June 4, 1770

In Whitsunday Passage, Queensland

Monday, 4th. Winds at South-South-East and South-East, a Gentle breeze and Clear weather. In the P.M. Steerd thro' the passage which we found from 3 to 6 or 7 Miles broad, and 8 or 9 Leagues in length, North by West 1/2 West and South by East 1/2 East. It is form'd by the Main on the West, and by Islands on the East, one of which is at least 5 Leagues in length. Our Depth of Water in running thro' was between 25 and 20 fathoms; everywhere good Anchorage; indeed the whole passage is one Continued safe Harbour, besides a Number of small Bays and Coves on each side, where ships might lay as it where in a Bason; at least so it appear'd to me, for I did not wait to Examine it, as having been in Port so lately, and being unwilling to loose the benefit of a light Moon. The land, both on the Main and Islands, especially on the former, is Tolerably high, and distinguished by Hills and Vallies, which are diversified with Woods and Lawns that looked green and pleasant. On a Sandy beach upon one of the Islands we saw 2 people and a Canoe, with an outrigger, which appeared to be both Larger and differently built to any we have seen upon the Coast. At 6 we were nearly the length of the North end of the Passage; the North Westermost point of the Main in sight bore North 54 degrees West, and the North end of the Island North-North-East, having an open Sea between these 2 points. [This passage I have named Whitsundays Passage, as it was discover'd on the day the Church commemorates that Festival, and the Isles which form it, Cumberland Isles, in honour of His Royal Highness the Duke of Cumberland. [Henry Frederick, Duke of Cumberland, was a younger brother of George III] We kept under an Easey Sail and the Lead going all Night, having 21, 22, and 23 fathoms, at the distance of 3 Leagues from the land. At daylight A.M. we were abreast of the point above mentioned, which is a lofty promontory; that I named Cape Gloucester, [William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, a younger brother of George III] (Latitude 19 degrees 57 minutes South, Longitude 211 degrees 54 minutes West). It may be known by an Island which lies out at Sea North by West 1/2 West, 5 or 6 Leagues from it; this I called Holbourn Isle. [Admiral Francis Holbourne commanded the fleet in North America in which Cook served in 1757] There are also Islands laying under the Land between it and Whitsundays Passage. On the West side of the Cape the Land Trends away South-West and South-South-West, and forms a deep bay. The Sand in the bottom of this bay I could but just see from the Masthead; it is very low, and is a Continuation of the same low land as is at the bottom of Repulse Bay. Without Waiting to look into this bay, which I called Edgcumbe Bay, [In Port Denison, on the western side of Edgcumbe Bay, is the rising town of Bowen, the port of an agricultural district. There is good coal in the vicinity. Captain G. Edgcumbe commanded the Lancaster in the fleet in North America in 1758 in which Cook served. Afterwards Earl of Mount Edgcumbe]. We continued our Course to the Westward.

The notes in [ ] are by W H Wharton in 1893.

On his voyage up the east coast until this point, Cook had already named Botany Bay, Port Jackson, Port Stephens, Cape Byron (for Commodore John Byron, commander of the Dolphin on its first circumnavigation of the world from 1764 to 1766), Mount Warning, Moreton Bay, (originally Morton, named for Lord Morton, president of the Royal Society) and the Glasshouse Mountains.

But as Tony Horwitz says in his book ‘Into the Blue’: “One of the ironies of Cook’s voyages is that a man who charted and named more of the world than any navigator in history has few places of consequence called after him.”

Portrait of Henry Duke of Cumberland, brother of King George III by Thomas Gainsborough, 1777

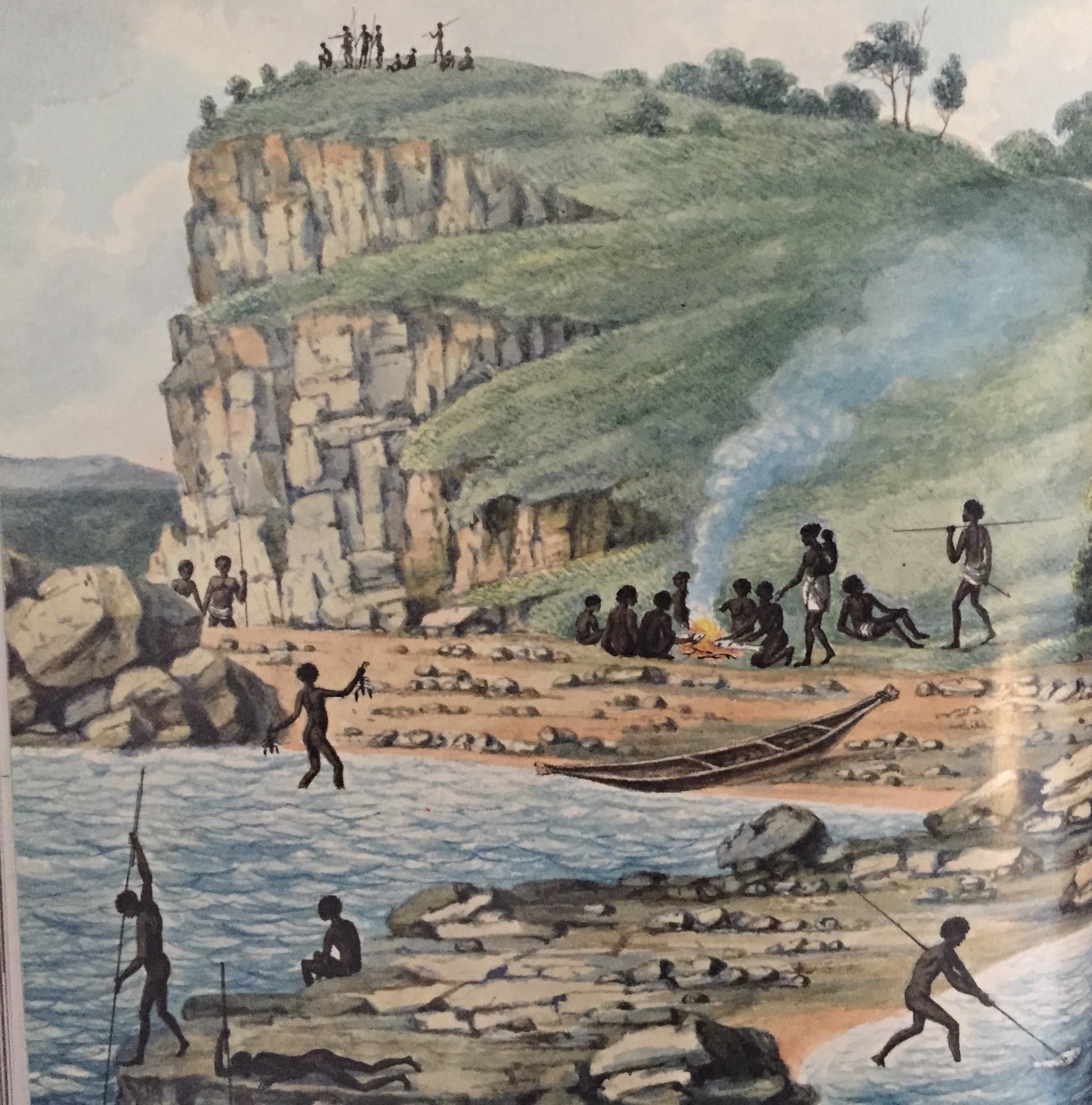

Aboriginals painting by Joseph Lycett c.1817 NLA

June 5, 1770

Portrait of botanist Joseph Banks by Joshua Reynolds

Tuesday, 5th. Winds between the South and East, a Gentle breeze, and Serene weather. At 6 a.m. we were abreast of the Western point of Land above mentioned, distant from it 3 Miles, which I have named Cape Upstart, because being surrounded with low land it starts or rises up singley at the first making of it (Latitude 19 degrees 39 minutes South, Longitude 212 degrees 32 minutes West); it lies West-North-West 14 Leagues from Cape Gloucester, and is of a height sufficient to be seen 12 Leagues; but it is not so much of a Promontory as it appears to be, because on each side of it near the Sea is very low land, which is not to be seen unless you are pretty well in with the Shore. Inland are some Tolerable high hills or mountains, which, like the Cape, affords but a very barren prospect. Having past this Cape, we continued standing to the West-North-West as the land lay, under an easey Sail, having from 16 to 10 fathoms, until 2 o'Clock a.m., when we fell into 7 fathoms, upon which we hauled our wind to the Northward, judging ourselves to be very near the land; as so we found, for at daylight we were little more than 2 Leagues off. What deceived us was the Lowness of the land, which is but very little higher than the Surface of the Sea, but in the Country were some hills. At and before Noon some very large smokes were Seen rise up out of the low land. At sun rise I found the Variation to be 5 degrees 35 minutes Easterly; at sun set last night the same Needle gave near 9 degrees. This being Close under Cape Upstart, I judged that it was owing to Iron ore or other Magnetical Matter Lodged in the Earth.

Banks’ Journal

5. at noon one large fire was seen. Several Cuttle bones and 2 Sea Snakes swam past the ship. In the Even the Thermometer was at 74 and the air felt to us hotter than we have felt it on the coast before. Many Clouds of a thin scum lay floating upon the water the same as we have before seen off Rio de Janiero; some few flying fish also.

James Cook was born on 7 November 1728 at Maron-in-Cleveland, Yorkshire. He died on 14 Feb 1779 in Hawaii from a stab wound.

From “Endeavour” by Peter Aughton

He was apprenticed to a grocer in the nearby fishing village of Staithes and there he first felt the call of the sea. Within 18 months he had moved down the coast to Whitby where he signed on as a deckhand on a Whitby collier, At 26 he was offered his first ship but gave it up to join the Royal Navy as an able seaman. He obtained his master’s certificate in 1757 (aged 29). He was a close and silent man and seldom displayed his feelings. He was cautious by nature but always prepared to take calculated risks.

He met Essex girl Elizabeth Batts. They married in 1762, he was 34, she was 20. They set up home in Mile End Road in the East End.

Cook’s Endeavour Journal NLA

On Sunday morning July 14 1771 Cook was reunited with his family at his home in Mile End in London’s East End where he learned that during his absence two of his four children had died. Elizabeth was four and Joseph three weeks, born a day after the Endeavour had set sail. When Cook’s wife Elizabeth died in 1835 aged 86 she had outlived all of her six children. George was born days before Cook left on his second voyage in 1772 but died before his father returned, Nathaniel died at sea in a hurricane at the age of 16, Hugh died at 17 of scarlet fever. James who like his father rose to become a commander in the Royal Navy was lost at sea at the age of 30.

Admiralty teamed with the Royal Society to observe the passage of Venus across the face of the sun. (They thought the other countries would not realise it was also a voyage of discovery) And would leave the ship unmolested so they could all benefit from the results of the observation as it was designed to add to man’s knowledge of the universe.

Cook had secret orders to search for new lands in the Pacific Ocean to annex for the Crown.

The commander had to be an experienced naval officer, he required great qualities of leadership. He needed to be highly skilled and experience in seamanship to be able to keep his vessel away from danger in unknown and uncharted waters. He needed to be an expert navigator who could find his position on the surface of the globe at all times and who could calculate longitudes as well as latitudes. Ideally he needed to be a skilled cartographer so that he could make and supervise maps and charts of the southern continent. He had to be capable of finding fresh water, food and provisions for the ship in the vastness of the Pacific. He also needed to be an astronomer to help with the observation of the transit of Venus.

There was one qualification Cook did not have. He was not a commissioned officer and he was not born of the gentry. His father had been an obscure labourer in a remote part of England.

Cook was made a lieutenant. He would be referred to as captain.

Soon after his return to England in 1771 he was promoted to the rank of commander. He never actually held the rank of captain, but in 1775 was promoted to the higher rank of post-captain (Source / Google)

Painting of the Bark, Earl of Pembroke, later the Endeavour, in Whitby Harbour 1768 by Thomas Luny

June 6, 1770

Wednesday, 6th. Light Airs at East-South-East, with which we Steer'd West-North-West as the Land now lay; Course and distance saild since Yesterday noon West-North-West, 28 Miles. In this situation we had the Mouth of a Bay all open extending from South 1/2 East to South-West 1/2 South, distance 2 Leagues. This bay, which I named Cleveland Bay [now Townsville] appeared to be about 5 or 6 Miles in Extent every way. The East point I named Cape Cleveland, and the West, Magnetical Head or Island, as it had much the appearance of an Island; and the Compass did not traverse well when near it. They are both Tolerable high, and so is the Main Land within them, and the whole appeared to have the most rugged, rocky, and barren Surface of any we have yet seen. However, it is not without inhabitants, as we saw smoke in several places in the bottom of the bay. The Northermost land we had in sight at this time bore North-West; this we took to be an Island or Islands, for we could not trace the Main land farther than West by North.

Bank’s Journal

6. Land made in Barren rocky capes; one in particular which we were abreast of in the morn appeard much like Cape Roxent; at noon 3 fires upon it. Many Cuttle bones, Some sea weed and 2 or 3 Sea snakes were seen. In the evening it fell quite calm and I went out in the small Boat and shot nectris nugax but saw nothing remarkable on the water; the weather most sultry hot in an open boat.

Nectris nugax is a type of petrel.

The Endeavour

There was already an HMS Endeavour, so Cook’s Endeavour was named a Bark.

From Peter Aughton’s book “Endeavour“ :

Cook rejected any suggestion that one of the Navy’s smart frigates should be used. He wanted a vessel with a large storage capacity and shallow draught so that it could sail close to short in a few fathoms. His ideal vessel was the ‘cat-built’ bark used on the North Sea to carry coal from the Tyneside coal fields to the capital (London). He knew these vessels and was confident about handling them. The admiralty agreed and chose the Earl of Pembroke.

The Earl of Pembroke was built at Whitby in about 1765. She was 106 feet in length from stern to bowsprit, 29 feet 3 ins across the beam. Drew only 14 feet fully laden. Admiralty purchased her from Thomas Milner for £2800. She was refitted, completely re-rigged, given additional outside skin of thin planking over a layer of tarred felt and renamed as His Majesty’s bark the Endeavour.

Unlike the naval frigates of the time, she was squat, round and unadorned but ideally suited for sailing coastal waters. The arrangement of masts and rigging on the catbuilt bark was very similar to that of a navy three-master. She had cabin windows to port and starboard which were tastefully decorated on the outside and a row of five windows lined the rear of her stern cabin

Cook’s Endeavour Journal NLA explains

‘Cat built’ meant she had a blunt bow, broad stern, wide beam, shallow draught, flat bottomed hull, three masts and was lightly rigged. Cat was an acronym for Coal And Timber.

She was 32 m long, and 9 metres wide and weighed 400 tonnes, she was designed to carry coal, not passengers. Her transformation required radical work and took her original cost of £2307 to more than £8000. Carpenters at Deptford yard not far from Greenwich added an extra skin of planks underwater, studded with flat topped nails to offer protection from Teredo Navalis, a wood-eating shipworm found in warm climates. They sheathed the boom of the hull in copper and built an extra deck below the main deck and furnished it with a series of cabins. Her top speed was 7 knots, about 13 kph.

On 30 July 1768 The Endeavour left Deptford yard and sailed to Plymouth. Cook was unhappy with the trim: “His majestys bark the Endeavour under my command Swims too much by the Head, and there being no means left to bring her down by the stern, but taking in more iron ballast abaft’ he complained. “Please order her to be supplyd with as much as may be found necessary for that purpose.”

He also requested that a green baize floor cloth be fitted to the great cabin, and the Navy Board agreed to both requests.

June 7, 1770

Painting of The Endeavour by Samuel Atkins c,1794 from ‘Cook’s Endeavour Journal’ NLA

Thursday, 7th. Light Airs between the South and East, with which we steer'd West-North-West, keeping the Main land on board, the outermost part of which at sun set bore from us West by North; but without this lay high land, which we took to be Islands. At daylight A.M. we were the Length of the Eastern part of this Land, which we found to Consist of a Group of Islands [Palm Islands] laying about 5 Leagues from the Main. We being at this time between the 2, we continued advancing Slowly to the North-West until noon, at which time we were by observation in the Latitude of 18 degrees 49 minutes, and about 5 Leagues from the Main land, the North-West part of which bore from us North by West 1/2 West, the Island extending from North to East; distance of the nearest 2 Miles. Cape Cleveland bore South 50 degrees East, distant 18 Leagues. Our Soundings in the Course of this day's Sail were from 14 to 11 fathoms.

Banks’ Journal

Sailing between the main and Islands the main rose steep from the Water rocky and barren. Just about sun rise a shoal of fish about the size of and much like flounders but perfectly white went by the ship. At noon the Islands had mended their appearance and people were seen upon them; the Main as barren as ever with several fires upon it, one vastly large. After dinner an appearance very much like Cocoa nut trees tempted us to hoist out a boat and go ashore, where we found our supposd Cocoanut trees to be no more than bad Cabbage trees. The Countrey about them was very stoney and barren and it was almost dark when we got ashsore; we made a shift however to gather 14 or 15 new plants after which we repaird to our boats, but scarce were they put off from the shore when an Indian came very near it and shouted to us very loud; it was so dark that we could not see him, we however turnd towards the shore by way of seeing what he wanted with us, but he I suppose ran away or hid himself immediately for we could not get a sight of him.

Banks kept his Journal in normal time, ie a day began and ended at midnight. This explains why his dates are different from Cook’s, who kept ship’s time from noon to noon.

Peter Aughton in “Endeavour” writes,

Joseph Banks and his Suite of 7 together with their luggage, requested to join the voyage, recommended by the Royal Society of which he was a Fellow.

Owner of a large fortune, he was a gentleman adventurer belonging to the English Aristocracy. He was 25 and had inherited a sizeable part of Lincolnshire and an income of £6,000 per year. He had already crossed the Atlantic to Newfoundland on a scientific expedition. He was a collector of flora and fauna of all known species.

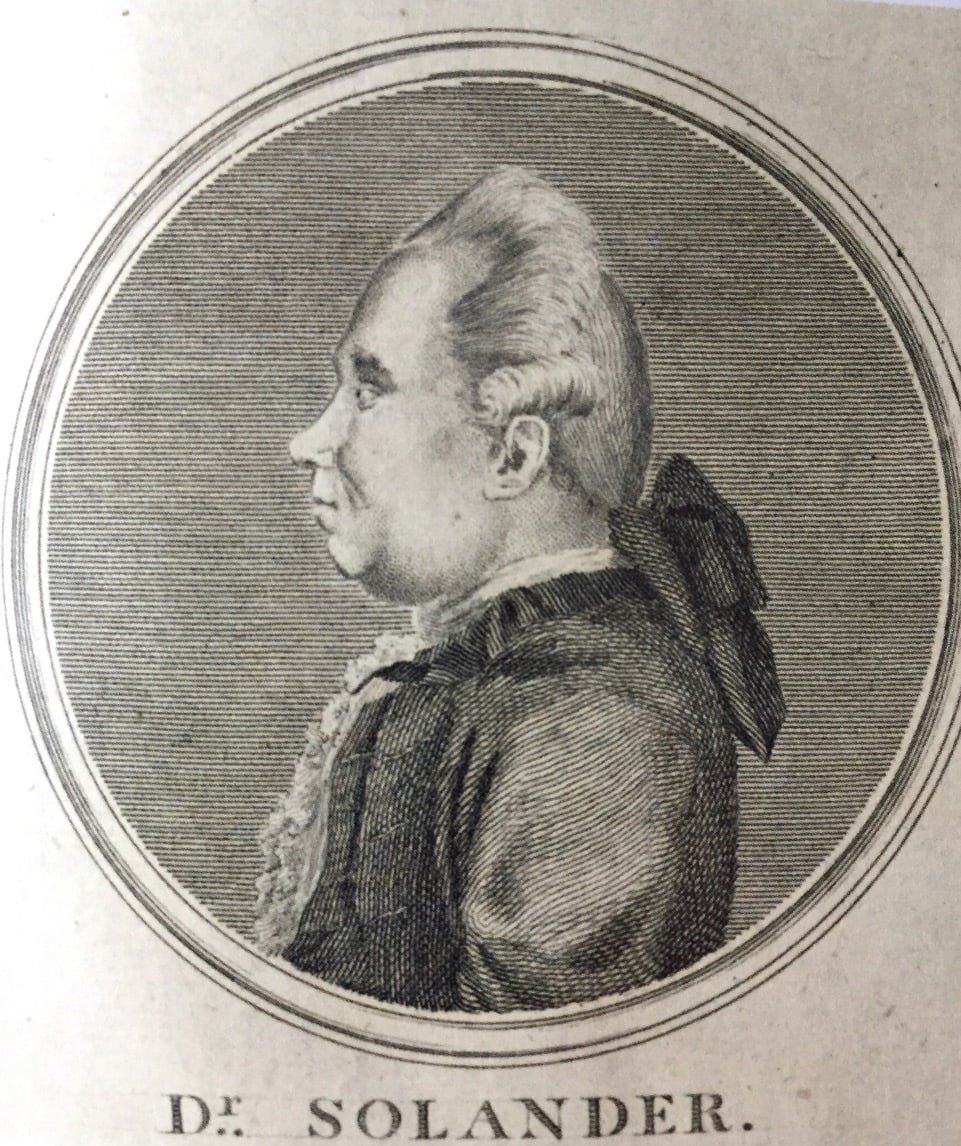

The Swedish botanist Count Carolus Linneaus had published a system of classification which bears his name. The Linnean system was introduced to England about 1760 by one of his pupils, Dr Daniel Carl Solander. One of his earliest converts was Joseph Banks. The Swedish doctor joined Banks’s party which also included two artists, a secretary, four servants and two hunting dogs.

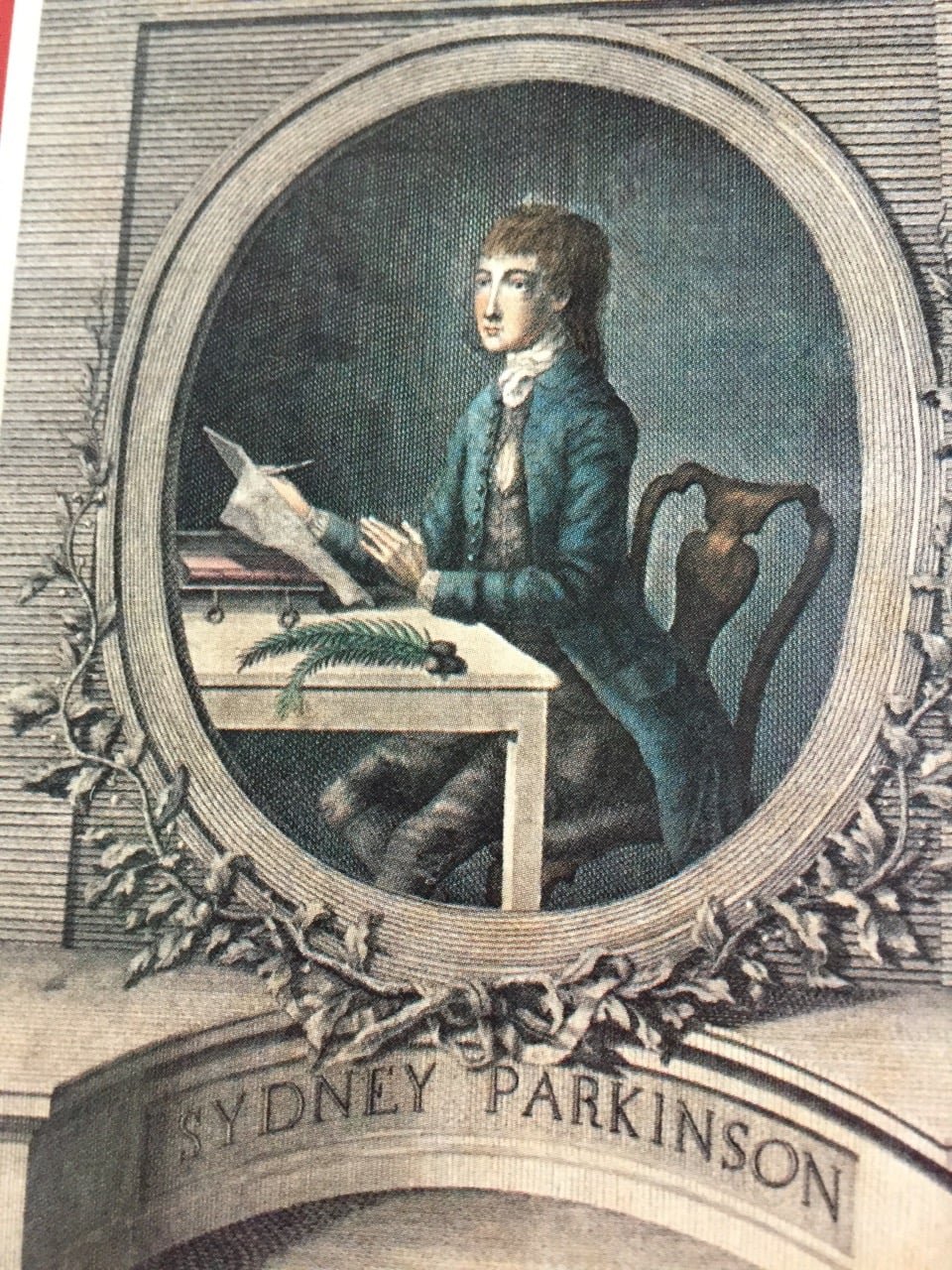

The artists were Sydney Parkinson, son of a Quaker brewer from Edinburgh, and Alexander Buchan. Parkinson was a fine draughtsman whose job was to draw the specimen which Banks and Solander were going to collect. He made 1,332 drawings and his journal was published posthumously.

Cook’s Endeavour Journal – the inside story NLA

By the time the Endeavour returned to England, its hold was filled with 30,382 plant specimens that Banks and Solander had collected. The two would collect more than 1400 new species, increasing the number of known plant species by 10 percent. Banks’ legacy was so large that Carl Linnaeus later proposed the new land be called Banksia.

Throughout the voyage Banks and Solander would press and dry their plant specimens between a large supply of remaindered sheets of Milton’s Paradise Lots.

Buchan was also a skilled artist but his talents were of the landscape artist.

Since the growth of the African slave trade it was essential for fashionable gentlemen of Banks’ fortune to have at least one black amongst their retinue, so he had two black servants, and their names, conferred by himself, were Thomas Richmond and George Dorlton. The other two, James Roberts and Peter Briscoe were from his Lincolnshire estates at Revesby.

Banks and Cook were from opposite ends of the rigid English social spectrum. It was to the credit of both and no small factor in the success of the voyage that they formed an immediate liking for each other. Banks’ journal always refereed to Cook in the highest terms as ‘the captain’ and Cook referred to his aristocratic passenger as ‘Mr Banks’.

On 14 August Cook was almost ready to sail: “Despatched an express to London for Mr Banks and Dr Solander to join the ship, their servants and baggage being already on board’.

Joseph Banks was enjoying a night at the opera with a lady friend Miss Harriet Blosset. He was very taken with her. ‘she possessed extraordinary beauty and every accomplishment with a fortune of ten thousand pounds’. She was blissfully ignorant that her wealthy escort was leaving on the morrow for the Terra Australis Incognita and only discovered it the following morning. Unreliable sources said they were engaged and that he left a ring with her guardian to claim her on his return.

June 8, 1770

Portrait of John Montague, Earl of Sandwich

Friday, 8th. Winds at South-South-East and South; first part light Airs, the remainder a Gentle breeze. In the P.M. we saw several large smokes upon the Main, some people, Canoes, and, as we thought, Cocoa Nut Trees upon one of the Islands; and, as a few of these Nutts would have been very acceptable to us at this Time, I sent Lieutenant Hicks ashore, with whom went Mr. Banks and Dr. Solander, to see what was to be got. In the Meantime we keept Standing in for the Island with the Ship. At 7 they returned on board, having met with Nothing worth Observing. The Trees we saw were a small kind of Cabbage Palms. They heard some of the Natives as they were putting off from the Shore, but saw none. After the Boat was hoisted in we stood away North by West for the Northermost land we had in sight, which we were abreast of at 3 o'Clock in the Morning, having passed all the Islands 3 or 4 hours before. This point I have named Point Hillock [Point Hillock is the east point of Hinchinbrook Island, which is separated from the main by a narrow and tortuous channel] on account of its Figure. The Land of this point is Tolerable high, and may be known by a round Hillock or rock that appears to be detached from the point, but I believe it joins to it. Between this Cape and Cape Cleveland the shore forms a Large bay, which I named Hallifax bay [The Earl of Halifax was Secretary of State 1763 to 1765]; before it lay the Groups of Islands before mentioned, and some others nearer the Shore. These Islands shelter the Bay in a manner from all Winds, in which is good Anchorage. The land near the Shore in the bottom of the bay is very low and Woody; but a little way back in the Country is a continued ridge of high land, which appear'd to be barren and rocky. Having passed Point Hillock, we continued standing to the North-North-West as the land Trended, having the Advantage of a light Moon. At 6 a.m. we were abreast of a point of Land which lies North by West 1/2 West, 11 Miles from Point Hillick; the Land between them is very high, and of a craggy, barren surface. This point I named Cape Sandwich [Earl of Sandwich was First Lord of the Admiralty 1763]; it may not only be known by the high, craggy land over it, but by a small Island which lies East one Mile from it, and some others about 2 Leagues to the Northward of it. From Cape Sandwich the Land trends West, and afterwards North, and forms a fine, Large Bay, which I called Rockingham Bay [The Marquis of Rockingham was Prime Minister 1765 to 1766] ; it is well Shelter'd, and affords good Anchorage; at least, so it appear'd to me, for having met with so little encouragement by going ashore that I would not wait to land or examine it farther, but continued to range along Shore to the Northward for a parcel of Small Islands [The Family Islands] laying off the Northern point of the Bay, and, finding a Channel of a Mile broad between the 3 Outermost and those nearer the Shore, we pushed thro'. While we did this we saw on one of the nearest Islands a Number of the Natives collected together, who seem'd to look very attentively upon the Ship; they were quite naked, and of a very Dark Colour, with short hair. At noon we were by observation in the Latitude of 17 degrees 59 minutes, and abreast of the North point of Rockingham Bay, which bore from us West 2 Miles. This boundry of the Bay is form'd by a Tolerable high Island, known in the Chart by the Name of Dunk Isle; it lays so near the Shore as not to be distinguished from it unless you are well in with the Land. Our depth of Water in the Course of this day's Sail was not more than 16, nor less than 7, fathoms [About here the Great Barrier Reefs begin to close in on the land. Cook kept so close to the latter that he was unconscious as yet of their existence; but he was soon to find them].

Banks’ Journal

8. Still sailing between the Main and Islands; the former rocky and high lookd rather less barren than usual and by the number of fires seemd to be better peopled. In the morn we passd within _ of a mile of a small Islet or rock on which we saw with our glasses about 30 men women and children standing all together and looking attentively at us, the first people we have seen shew any signs of curiosity at the sight of the ship.

Cook named Dunk Island after George Montague-Dunk, 2nd Earl of Halifax (a former First Lord of the Admiralty).

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich (13 November 1718 – 30 April 1792) was a British statesman who succeeded his grandfather as the Earl of Sandwich in 1729, at the age of ten. During his life, he held various military and political offices, including Postmaster General, First Lord of the Admiralty, and Secretary of State for the Northern Department. He is also known for the claim that he was the eponymous inventor of the sandwich. (Source / Wikipedia)

Cook’s Endeavour Journal - NLA

The crew would haul, pull, furl and set the sails, clambering up and down the riggings to make necessary adjustments and carry out repairs. Daily they would scrub the deck with sand and a holy stone (soft sandstone) before washing away the slurry and swabbing the timber dry. Clean the bright-work (varnished wood) guns and carriages and refill the water tanks.

Below decks the atmosphere was thick and putrid even though Cook had his men rig special sails to direct the wind into the living spaces and combat the ever-present dampness. The livestock, much to the crew’s relief, were penned on the upper deck.

On Tuesdays the crew cleaned their hammocks and aired their bedding. On Thursdays they washed their clothes. Owing to a lack of fresh water, clothing was often towed behind the ship. Men usually bathed once a week although they would have washed without soap. The Royal Navy did not introduce soap until 1796. The toilets were by and large self-cleaning. The two ‘seats of ease’ as they were called, were at the bow of the ship, positioned over the sea and exposed to every wave.

June 9, 1770

Anchored near Cape Grafton, Queensland

Saturday, 9th. Winds between the South and South-East, a Gentle breeze, and Clear weather, with which we steer'd North by West as the land lay. At 6 a.m. we were abreast of Some small Islands, which we called Frankland Isles, that lay about 2 Leagues from the Mainland, the Northern Point of which in sight bore North by West 1/2 West; but this we afterwards found to be an Island, [Fitzroy Island] tolerable high, and about 4 Miles in Circuit. It lies about 2 Miles from the Point on the Main between which we went with the ship, and were in the Middle of the Channell at Noon, and by observation in the Latitude of 16 degrees 55 minutes, where we had 20 fathoms of water. The point of land we were now abreast of I called Cape Grafton. [The Duke of Grafton was Prime Minister when Cook sailed] (Latitude 16 degrees 55 minutes South, Longitude 214 degrees 11 minutes West); it is Tolerable high, and so is the whole Coast for 20 Leagues to the southward, and hath a very rocky surface, which is thinly cover'd with wood. In the night we saw several fires along shore, and a little before noon some people.

Banks’ Journal

9. Countrey much the same as it was, hills near the sea high, lookd at a distance not unlike Mores or heaths in England but when you came nearer them were coverd with small trees; some few flatts and valleys lookd tolerably fertile. At noon a fire and some people were seen. After dinner came to an Anchor and went ashore, but saw no people. The countrey was hilly and very stony affording nothing but fresh water, at least that we found, except a few Plants that we had not before met with. At night our people caught a few small fish with their hooks and lines.

Wikipedia: Yarrabah is an Aboriginal community south of Cairns. On an evening in early June 1770, the Endeavour anchored near there. While James Cook had no luck in finding accessible fresh water, Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander added to their plant collection. There were no encounters with local Gunggandji people, but the Endeavour’s visit was recorded in nearby rock art.

Queensland Govt Department of Environment and Science

Lieutenant James Cook named the Frankland islands in 1770 in honour of two 18th century sailors—a Lord of the Admiralty and his nephew, both named Sir Thomas Frankland.

Cape Grafton was named after Augustus FitzRoy, 3rd Duke of Grafton, the British prime minister when Cook sailed. Cook set anchor two miles from the shore and briefly inspected the cape with botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander (Source / Wikipedia)

The Aboriginal community of Yarrabah is located here. It was founded by John Gribble in 1892

June 10 1770

Lieutenant James Cook named Low Isles and Cape Tribulation

Sunday, 10th. After hauling round Cape Grafton we found the land trend away North-West by West; 3 Miles to the Westward of the Cape is a Bay, wherein we Anchor'd, about 2 Miles from the Shore, in 4 fathoms, owsey bottom. The East point of the Bay bore South 74 degrees East, the West point South 83 degrees West, and a Low green woody Island laying in the Offing bore North 35 degrees East. The Island lies North by East 1/2 East, distance 3 or 4 Leagues from Cape Grafton, and is known in the Chart by the Name of Green Island. As soon as the Ship was brought to an Anchor I went ashore, accompanied by Mr. Banks and Dr. Solander; the first thing I did was to look for fresh Water, and with that View rowed out towards the Cape, because in the bottom of the bay was low Mangrove land, and little probability of meeting with any there. But the way I went I found 2 Small streams, which were difficult to get at on account of the Surf and rocks upon the Shore. As we came round the Cape we saw, in a sandy Cove, a small stream of Water run over the beach; but here I did not go in the boat because I found that it would not be Easey to land. We hardly advanced anything into the Country, it being here hilly, which were steep and rocky, and we had not time to Visit the Low lands, and therefore met with nothing remarkable. My intention was to have stay'd here at least one day, to have looked into the Country had we met with fresh water convenient, or any other Refreshment; but as we did not, I thought it would be only spending of time, and loosing as much of a light Moon to little purpose, and therefore at 12 o'Clock at night we weighed and stood away to the North-West, having at this time but little wind, attended with Showers of rain. [In the next bay west of where Cook anchored is Cairns, a small but rising town in the centre of a sugar-growing district]

At 4 the breeze freshned at South by East, with fair weather; we continued steering North-North-West 1/2 West as the Land lay, having 10, 12, and 14 fathoms, at a distance of 3 Leagues from the Land. At 11 we hauld off North, in order to get without a Small Low Island [Low Isles. There is now a lighthouse on them] which lay about 2 Leagues from the Main; it being about high Water, about the time we passed it, great part of it lay under water. About 3 Leagues to the North Westward of this Island, close under the Main land, is another Island, [Snapper Island] Tolerable high, which bore from us at Noon North 55 degrees West, distant 7 or 8 Miles; we being at this time in the Latitude of 16 degrees 20 minutes South, Cape Grafton bore South 29 degrees East, distant 40 Miles, and the Northermost point of Land in Sight North 20 degrees West, and in this Situation had 15 fathoms Water. The Shore between Cape Grafton and the above Northern point forms a large but not very deep Bay, which I named Trinity Bay, after the day on which it was discover'd; the North point Cape Tribulation, because here began all our Troubles. Latitude 16 degrees 6 minutes South, Longitude 214 degrees 39 minutes West.

Cook always used Ship's Time for his journal, beginning and ending his day at noon. This is why his afternoon comes before his morning reports.

The Endeavour was loaded and provisioned for an 18 month voyage.

Low Isles, off Port Douglas

From Peter Aughton’s “Endeavour”

The ship was fitted with twelve swivel guns and ten carriage guns with all the necessary powder and shot. The hold was loaded with eight tons of ballast and with several tons of coal for heating and cooking. There were spare timbers for spars and planking, barrels of tar and pitch, tools for carpenters, canvas for the sailmakers, hemp for the ropes and rigging, a ships’s forge. Tools and materials for all other shipboard crafts. 20 tons of ships biscuits and flour were loaded, 1200 gallons of beer,1600 gallons of spirits, 4000 pieces of salted beef and 6000 pieces of salted pork, 1500 pounds of sugar, suet, raisons, oatmeal, wheat, oil, vinegar, malt 160 pounds of mustard seed, 107 bushels of pease stored in butts, and a staggering 7860 pounds of a high-smelling fermented cabbage which the Germans called Sauerkraut. This was a ration of 80 pounds per man and it was thought to keep the dreaded scurvy away. The ship also carried iron nails, fishhooks, hatchets, scissors, red and blue beads, small mirrors and even a few dolls to charm the natives of the south sea islands and to barter with them for food and provisions. All these supplies with the possible exception of the 2 and a half tons of sauerkraut, were part of the standard rations for a naval vessel.

The ship carried 30 tonnes of water which would be supplemented at ports and rivers or collected during storms at sea by a system of sails and funnels. Also aboard were 3 cats, 17 sheep, 24 chickens, 4 pigs, Banks’s 2 dogs who slept on cushions in his cabin and a goat to supply milk for the officers’ coffee. She had earlier circumnavigated the globe with Capt Wallis.

The instruments were well above the standard supplies. Dr Knight’s newly patented azimuth compass of improved construction to find magnetic North was supplemented by a vertical compass to measure the angle of dip. An astronomical brass quadrant of 1 foot radius was supplied with a high quality sextant. Along with two astronomical telescopes provided by the Royal Society. There was a portable observatory made of wood and canvas. There were recording devices, an astronomical clock for accurate timekeeping supplied by the Royal Greenwich Observatory and two thermometers to help with the calibration of the clocks in the heat of the tropics. A complete Theodolite, a plane table, and a 2 foot brass scale, a double concave glass and a glass for tracing light rays.

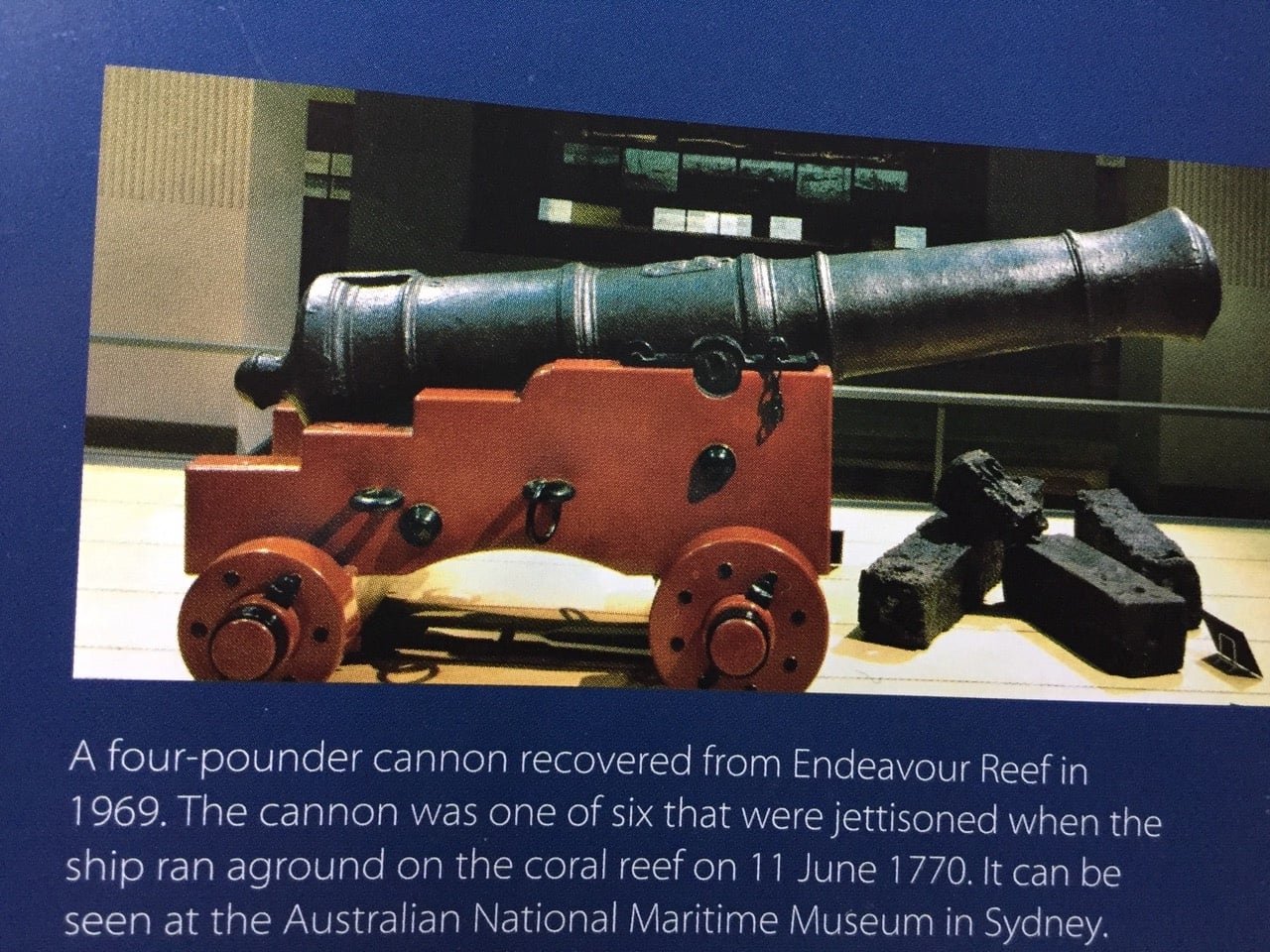

On this day, James Cook's Endeavour struck coral on the Great Barrier Reef. Here is Cook's account:

June 11, 1770

Monday, 11th. Wind at East-South-East, with which we steer'd along shore North by West at the distance of 3 or 4 Leagues off, having from 14 to 10 and 12 fathoms water. Saw 2 Small Islands in the Offing, which lay in the Latitude of 16 degrees 0 minutes South, and about 6 or 7 Leagues from the Main. At 6 the Northermost land in sight bore North by West 1/2 West, and 2 low, woody Islands, [Hope Islands] which some took to be rocks above Water, bore North 1/2 West. At this time we shortened Sail, and hauld off shore East-North-East and North-East by East, close upon a Wind. My intention was to stretch off all Night as well to avoid the danger we saw ahead as to see if any Islands lay in the Offing, especially as we now begun to draw near the Latitude of those discover'd by Quiros, which some Geographers, for what reason I know not, have thought proper to Tack to this land. Having the advantage of a fine breeze of wind, and a clear Moon light Night in standing off from 6 until near 9 o Clock, we deepned our Water from 14 to 21 fathoms, when all at once we fell into 12, 10 and 8 fathoms. At this time I had everybody at their Stations to put about and come to an Anchor; but in this I was not so fortunate, for meeting again with Deep Water, I thought there could be no danger in standing on [The ship passed just northward of Pickersgill Reef.]. Before 10 o'Clock we had 20 and 21 fathoms, and Continued in that depth until a few minutes before 11, when we had 17, and before the Man at the Lead could heave another cast, the Ship Struck and stuck fast. Immediately upon this we took in all our Sails, hoisted out the Boats and Sounded round the Ship, and found that we had got upon the South-East Edge of a reef of Coral Rocks, having in some places round the Ship 3 and 4 fathoms Water, and in other places not quite as many feet, and about a Ship's length from us on the starboard side (the Ship laying with her Head to the North-East) were 8, 10, and 12 fathoms. As soon as the Long boat was out we struck Yards and Topmast, and carried out the Stream Anchor on our Starboard bow, got the Coasting Anchor and Cable into the Boat, and were going to carry it out in the same way; but upon my sounding the 2nd time round the Ship I found the most water a Stern, and therefore had this Anchor carried out upon the Starboard Quarter, and hove upon it a very great Strain; which was to no purpose, the Ship being quite fast, upon which we went to work to lighten her as fast as possible, which seem'd to be the only means we had left to get her off. As we went ashore about the Top of High Water we not only started water, but threw overboard our Guns, Iron and Stone Ballast, Casks, Hoop Staves, Oil Jarrs, decay'd Stores, etc.; many of these last Articles lay in the way at coming at Heavier. All this time the Ship made little or no Water. At 11 a.m., being high Water as we thought, we try'd to heave her off without Success, she not being afloat by a foot or more, notwithstanding by this time we had thrown overboard 40 or 50 Tuns weight. As this was not found sufficient we continued to Lighten her by every method we could think off; as the Tide fell the ship began to make Water as much as two pumps could free: at Noon she lay with 3 or 4 Streakes heel to Starboard; Latitude observed 15 degrees 45 minutes South.

Pedro Fernandes de Queirós (Spanish: Pedro Fernández de Quirós) (1563–1614) was a Portuguese navigator in the service of Spain best known for his involvement with Spanish voyages of discovery in the Pacific Ocean and for leading a 1605–1606 expedition which crossed the Pacific in search of Terra Australis (Source. /Wikipedia)

Banks’ Journal 10 June 1770 (Banks kept normal time, not ship’s time)

10. Just without us as we lay at an anchor was a small sandy Island laying upon a large Coral shoal, much resembling the low Islands to the eastward of us but the first of the kind we had met with in this part of the South Sea. Early in the morn we weighd and saild as usual with a fine breeze along shore, the Countrey hilly and stoney. At night fall rocks and sholes were seen ahead, on which the ship was put upon a wind off shore. While we were at supper she went over a bank of 7 or 8 fathom water which she came upon very suddenly; this we concluded to be the tail of the Sholes we had seen at sunset and therefore went to bed in perfect security, but scarce were we warm in our beds when we were calld up with the alarming news of the ship being fast ashore upon a rock, which she in a few moments convincd us of by beating very violently against the rocks. Our situation became now greatly alarming: we had stood off shore 3 hours and a half with a plesant breeze so knew we could not be very near it: we were little less than certain that we were upon sunken coral rocks, the most dreadfull of all others on account of their sharp points and grinding quality which cut through a ships bottom almost immediately. The officers however behavd with inimitable coolness void of all hurry and confusion; a boat was got out in which the master went and after sounding round the ship found that she had ran over a rock and consequently had Shole water all round her. All this time she continued to beat very much so that we could hardly keep our legs upon the Quarter deck; by the light of the moon we could see her sheathing boards &c. floating thick round her; about 12 her false keel came away.

Cooks Endeavour Journal NLA

In an effort to lighten the ship and help her float free, the crew jettisoned six cannon along with iron and stone ballast, casks, ruined stores and drinking water. The Endeavour was 40 or 50 tonnes lighter but still she would not budge. The crew attached buoys to the six cannon, intending to retrieve them later. The operation proved unfeasible and the guns were abandoned where they sank. In 1969 searchers using an advanced magnetometer found the cannon and the iron ballast.

June 12, 1770

Tuesday, 12th. Fortunately we had little wind, fine weather, and a smooth Sea, all this 24 Hours, which in the P.M. gave us an Opportunity to carry out the 2 Bower Anchors, one on the Starboard Quarter, and the other right a Stern, got Blocks and Tackles upon the Cables, brought the falls in abaft and hove taught. By this time it was 5 o'Clock p.m.; the tide we observed now begun to rise, and the leak increased upon us, which obliged us to set the 3rd Pump to work, as we should have done the 4th also, but could not make it work. At 9 the Ship righted, and the Leak gain'd upon the Pumps considerably. This was an alarming and, I may say, terrible circumstance, and threatened immediate destruction to us. However, I resolv'd to risque all, and heave her off in case it was practical, and accordingly turn'd as many hands to the Capstan and Windlass as could be spared from the Pumps; and about 20 Minutes past 10 o'Clock the Ship floated, and we hove her into Deep Water, having at this time 3 feet 9 Inches Water in the hold. This done I sent the Long boat to take up the Stream Anchor, got the Anchor, but lost the Cable among the Rocks; after this turn'd all hands to the Pumps, the Leak increasing upon us.

A mistake soon after hapned, which for the first time caused fear to approach upon every man in the Ship. The man that attended the well took the Depth of water above the Ceiling; he, being relieved by another who did not know in what manner the former had sounded, took the Depth of water from the outside plank, the difference being 16 or 18 inches, and made it appear that the leak had gained this upon the pumps in a short time. This mistake was no sooner cleared up than it acted upon every man like a Charm; they redoubled their vigour, insomuch that before 8 o'clock in the morning they gained considerably upon the leak [The circumstance related in this paragraph is from the Admiralty copy] We now hove up the Best Bower, but found it impossible to save the small Bower, so cut it away at a whole Cable; got up the Fore topmast and Foreyard, warped the Ship to the South-East, and at 11 got under sail, and stood in for the land, with a light breeze at East-South-East. Some hands employ'd sewing Oakham, Wool, etc., into a Lower Steering sail to fother the Ship; others employ'd at the Pumps, which still gain'd upon the Leak.

Peter Aughton’s ‘Endeavour’

Fothering was the method of plugging a hole by passing beneath the affected area a sail billed with wool, dung from any animals aboard and oakum (tar-filled rope fibre). The idea was that the material would be sucked into the opening and stop, or at least slow, the leak. The work was supervised by midshipman Jonathan Monkhouse whose brother had furthered a ship wrecked off the coast of Virginia.

Banks’ Journal

About one the water was faln so low that the Pinnace touchd ground as he lay under the ships bows ready to take in an anchor, after this the tide began to rise and as it rose the ship workd violently upon the rocks so that by 2 she began to make water and increasd very fast. At night the tide almost floated her but she made water so fast that three pumps hard workd could but just keep her clear and the 4th absolutely refusd do deliver a drop of water. Now in my own opinion I intirely gave up the ship and packing up what I thought I might save prepard myself for the worst.

The most critical part of our distress now aproachd: the ship was almost afloat and every thing ready to get her into deep water but she leakd so fast that with all our pumps we could just keep her free: if (as was probable) she should make more water when hauld off she must sink and we well knew that our boats were not capable of carrying us all ashore, so that some, probably the most of us, must be drownd: a better fate maybe than those would have who should get ashore without arms to defend themselves from the Indians or provide themselves with food, on a countrey where we had not the least reason to hope for subsistance had they even every convenence to take it as netts &c, so barren had we always found it; and had they even met with good usage from the natives and food to support them, debarrd from a hope of ever again seing their native countrey or conversing with any but the most uncivilizd savages perhaps in the world.

Fear of Death now stard us in the face; hopes we had none but of being able to keep the ship afloat till we could run her ashore on some part of the main where out of her materials we might build a vessel large enough to carry us to the East Indies. At 10 O'Clock she floated and was in a few minutes hawld into deep water where to our great satisfaction she made no more water than she had done.

June 13, 1770

The Endeavour was stuck on the reef.

Wednesday, 13th. In the P.M. had light Airs at East-South-East, with which we keept edging in for the Land. Got up the Maintopmast and Mainyard, and having got the Sail ready for fothering of the Ship, we put it over under the Starboard Fore Chains, where we suspected the Ship had suffer'd most, and soon after the Leak decreased, so as to be kept clear with one Pump with ease; this fortunate circumstance gave new life to everyone on board.

It is much easier to conceive than to describe the satisfaction felt by everybody on this occasion. But a few minutes before our utmost Wishes were to get hold of some place upon the Main, or an island, to run the Ship ashore, where out of her Materials we might build a Vessel to carry us to the East Indies; no sooner were we made sencible that the outward application to the Ship's bottom had taken effect, than the field of every Man's hopes inlarged, so that we thought of nothing but ranging along Shore in search of a Harbour, when we could repair the Damages we had sustained.

[The foregoing paragraph is from the Admiralty copy. The situation was indeed sufficiently awkward. When it is considered that the coast was wholly unknown, the natives decidedly hostile, the land unproductive of any means of subsistence, and the distance to the nearest Dutch settlements, even if a passage should be found south of New Guinea, 1500 miles, there was ample cause for apprehension if they could not save the ship. Knowing what we now know, that all off this coast is a continuous line of reefs and shoals, Cook's action in standing off might seem rash. But he knew nothing of this. There was a moon; he reduced sail to double reefed topsails with a light wind, as the log tells us, and with the cumbrous hempen cables of the day, and the imperfect means of heaving up the anchor, he was desirous of saving his men unnecessary labour. Cook was puzzled that the next tide did not, after lightening the ship, take him off; but it is now known that on this coast it is only every alternate tide that rises to a full height, and as he got ashore nearly at the top of the higher of the two waters he had to wait twenty-four hours until he got a similar rise. Lucky was it for them that the wind was light.

Usually at this season the trade wind is strong, and raises a considerable sea, even inside the Barrier. Hawkesworth or Banks makes the proposition to fother the ship emanate from Mr. Monkhouse; but it is scarcely to be supposed that such a perfect seaman as Cook was not familiar with this operation, and he merely says that as Mr. Monkhouse had seen it done, he confided to him the superintendence of it, as of course the Captain had at such a time many other things to do than stand over the men preparing the sail. In 1886 the people of Cooktown were anxious to recover the brass guns of the Endeavour which were thrown overboard, in order to place them as a memento in their town; but they could not be found, which is not altogether surprising.]

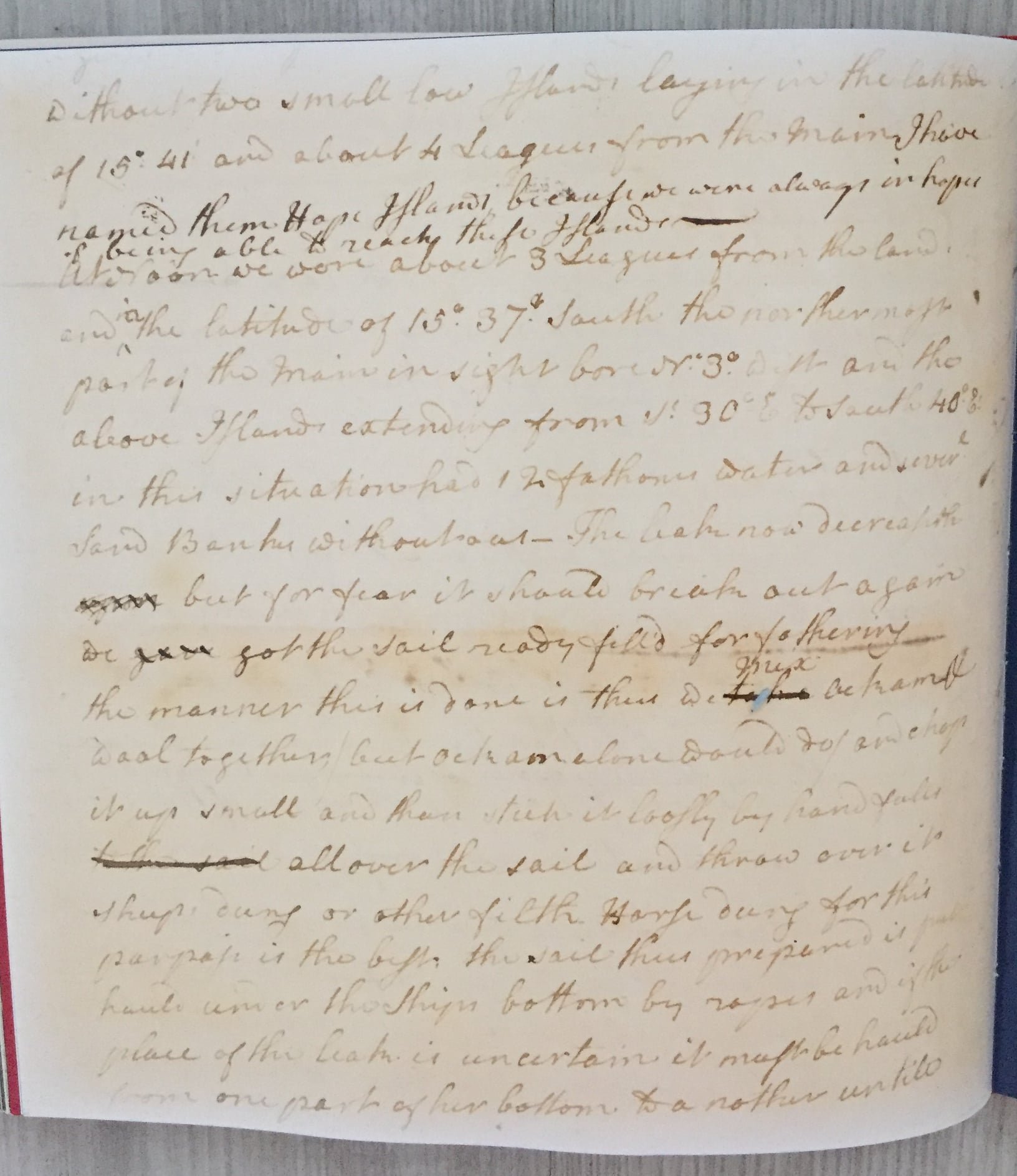

In justice to the Ship's Company, I must say that no men ever behaved better than they have done on this occasion; animated by the behaviour of every Gentleman on board, every man seem'd to have a just sence of the Danger we were in, and exerted himself to the very utmost. The Ledge of Rocks, or Shoal, we have been upon, lies in the Latitude of 15 degrees 45 minutes, and about 6 or 7 Leagues from the Main land; but this is not the only Shoal that lay upon this part of the Coast, especially to the Northward, and one which we saw to the Southward, the tail of which we passed over when we had the uneven Soundings 2 hours before we Struck. A part of this Shoal is always above Water, and looks to be white Sand; part of the one we were upon was dry at low Water, and in that place consists of Sand and stones, but every where else Coral Rocks. At 6 we Anchored in 17 fathoms, about 5 or 6 Leagues from the land, and one from the Shoal. At this time the Ship made about 15 Inches Water per hour. At 6 a.m. weigh'd and stood to the North-West, edging in for the land, having a Gentle breeze at South-South-East. At 9 we past close without 2 small low Islands, laying in the Latitude of 15 degrees 41 minutes, and about 4 Leagues from the Main; I have named them Hope Islands, because we were always in hopes of being able to reach these Islands. At Noon The Leak now decreaseth, but for fear it should break out again we got the Sail ready fill'd for fothering; the manner this is done is thus: We Mix Oacham and Wool together (but Oacham alone would do), and chop it up Small, and then stick it loosely by handfulls all over the Sail, and throw over it Sheep dung or other filth. Horse Dung for this purpose is the best. The Sail thus prepared is hauld under the Ship's bottom by ropes, and if the place of the Leak is uncertain, it must be hauld from one part of her bottom to another until one finds the place where it takes effect. While the Sail is under the Ship the Oacham, etc., is washed off, and part of it carried along with the water into the Leak, and in part stops up the hole. Mr. Monkhouse, one of my Midshipmen, was once in a Merchant Ship which Sprung a Leak, and made 48 Inches Water per hour; but by this means was brought home from Virginia to London with only her proper crew; to him I gave the direction of this, who executed it very much to my satisfaction.

(Cook is still keeping ship’s time, the day beginning at 12 noon and ending at 12 midnight.

At sea, a league is 3.45 miles or 5.5 kms.

Oakam is tar-filled rope fibre.)

Banks’ Journal

12. The people who had been 24 hours at exceeding hard work now began to flag; myself unusd to labour was much fatigued and had laid down to take a little rest, was awakd about 12 with the alarming news of the ships having gaind so much upon the Pumps that she had four feet water in her hold: add to this that the wind blew of the land a regular land breeze so that all hopes of running her ashore were totaly cut off. This however acted upon every body like a charm: rest was no more thought of but the pumps went with unwearied vigour till the water was all out which was done in a much shorter time than was expected, and upon examination it was found that she never had half so much water in her as was thought, the Carpenter having made a mistake in sounding the pumps.

We now began again to have some hopes and to talk of getting the ship into some harbour as we could spare hands from the pumps to get up our anchors; one Bower however we cut away but got the other and three small anchors far more valuable to us than the Bowers, as we were obligd immediately to warp her to windward that we might take advantage of the sea breeze to run in shore.

One of our midshipmen now proposd an expedient which no one else in the ship had seen practisd, tho all had heard of it by the name of fothering a ship, by the means of which he said he had come home from America in a ship which made more water than we did; nay so sure was the master of that ship of his expedient that he took her out of harbour knowing how much water she made and trusting intirely to it. He was immediately set to work with 4 or 5 assistants to prepare his fother which he did thus. He took a lower studding sail and having mixd together a large quantity of Oakum chopd fine and wool he stickd it down upon the sail as loosely as possible in small bundles each about as big as his fist, these were rangd in rows 3 or 4 inches from each other: this was to be sunk under the ship and the theory of it was this, where ever the leak was must be a great suction which would probably catch hold of one or other of these lumps of Oakum and wool and drawing it in either partly or intirely stop up the hole. While this work was going on the water rather gaind on those who were pumping which made all hands impatient for the tryal. In the afternoon the ship was got under way with a gentle breeze of wind and stood in for the land; soon after the fother was finishd and applyd by fastning ropes to each Corner, then sinking the sail under the ship and with these ropes drawing it as far backwards as we could; in about an hour to our great surprize the ship was pumpd dry and upon letting the pumps stand she was found to make very little water, so much beyond our most sanguine Expectations had this singular expedient succeeded. At night came to an anchor, the fother still keeping her almost clear so that we were in an instant raisd from almost despondency to the greatest hopes: we were now almost too sanguine talking of nothing but getting her into some harbour where we might lay her ashore and repair her, or if we could not find such a place we little doubted to the East indies.

During the whole time of this distress I must say for the credit of our people that I beleive every man exerted his utmost for the preservation of the ship, contrary to what I have universaly heard to be the behavior of sea men who have commonly as soon as a ship is in a desperate situation began to plunder and refuse all command. This was no doubt owing intirely to the cool and steady conduct of the officers, who during the whole time never gave an order which did not shew them to be perfectly composd and unmovd by the circumstances howsoever dreadfull they might appear.

"Endeavour” by Peter Aughton

The Endeavour’s lower studding sail was taken on deck and prepared by sewing into it tufts of oakum and wool. Each tuft was about the size of a fist and arranged in rows a few inches apart. Ideally sheep and horse dung would be thrown over the sail but the ships goat and the greyhound gladly supplied a substitute. The fothering sail then had to be worked around and under the ship near the starboard fore chains where the hull was damaged. The theory was that the pressure of the water entering the leak would cause the oakum to flow into the hole and plug it.

“Into the Blue” by Tony Horwitz

Cook set his sights on two barren sandbars naming them Hope ‘because we were always in hopes of being able to reach these islands.' Unable to do so, he pinned his hopes instead on a harbour he named Weary Bay. But the bay was too shallow. At sunset men in the pinnace found a river mouth deep enough to bring the ship in. but the weather turned so wet and blowy that the badly damaged ship ‘would not work’ Cook wrote. Finally on June 18, a full week after striking the reef Cook sailed into the narrow river.

June 14 1770

The Master, Robert Molyneux

Three small boats sketch by Sydney Parkinson, from “Endeavour” by Peter Aughton

Thursday, 14th. P.M., had a Gentle breeze at South-East by East. Sent the Master, with 2 Boats as well, to sound ahead of the Ship, as to look out for a Harbour where we could repair our defects, and put the Ship on a proper Trim, both of which she now very much wanted. At 3 saw an Opening that had the appearance of a Harbour; stood off and on while the Boats were examining it, who found that there was not a sufficient depth of Water for the Ship. By this time it was almost sun set, and seeing many shoals about us we Anchored in 4 fathoms about 2 miles from the Shore. At 8 o'clock the Pinnace, in which was one of the Mates, return'd on board, and reported that they had found a good Harbour [Cook Harbour, Endeavour River.] about 2 Leagues to leeward. In consequence of this information we, at 6 a.m., weigh'd and run down to it, first sending 2 Boats ahead to lay upon the Shoals that lay in our way; and notwithstanding this precaution, we were once in 3 fathoms with the Ship. Having pass'd these Shoals, the Boats were sent to lay in the Channell leading into the Harbour. By this time it begun to blow in so much that the Ship would not work, having missed stays Twice; and being entangled among Shoals, I was afraid of being drove to Leeward before the Boats could place themselves, and therefore Anchoredd in 4 fathoms about a Mile from the Shore, and then made the Signal for the Boats to come on board, after which I went myself and Buoy'd the Channell, which I found very narrow, and the Harbour much smaller than I had been told, but very convenient for our Purpose. At Noon Latitude observed 15 degrees 26 minutes South.

The Master was Robert Molyneux. He died aged 25 as the ship left Table Bay, South Africa.

Peter Aughton

The Endeavour carried three small boats, a pinnace, reserved for the use of the ship’s captain, a yawl – just large enough to carry four rowers and three passengers and a long boat for carrying water and stores. All three had sails and oars

A fathom is a unit of length equal to six feet (1.8 metres).

Banks’ Journal

The Pinnace however which had gone far ahead was not returnd, nor did she till nine O'Clock, when she reported that she had found just the place we wanted, in which the tide rose sufficiently and there was every natural convenience that could be wishd for either laying the ship ashore or heaving her down. This was too much to be beleivd by our most sanguine wishes: we however hopd that the place might do for us if not so much as we had been told yet something to better our situation, as yet but precarious, having nothing but a lock of Wool between us and destruction.

June 15, 1770

Friday, 15th. A fresh Gale at South-East and Cloudy weather, attended with Showers of Rain. In the Night, as it blow'd too fresh to break the Ship loose to run into the Harbour, we got down the Topgallant yards, unbent the Mainsail, and some of the Small sails; got down the Foretopgallant mast, and the Jibb Boom and Spritsailyard in, intending to lighten the Ship Forward as much as possible, in order to lay her ashore to come at the Leak.

Banks’ Journal

14. Very fresh Sea breeze. A boat was sent ahead to shew us the way into the harbour, but by some mistake of signals we were obligd to come to an anchor again of the mouth of it without going in, where it soon blew too fresh for us to Weigh. We now began to consider our good fortune; had it blown as fresh the day before yesterday or before that we could never have got off but must inevitably have been dashd to peices on the rocks. The Captn and myself went ashore to view the Harbour and found it indeed beyond our most sanguine wishes: it was the mouth of a river the entrance of which was to be sure narrow enough and shallow, but when once in the ship might be moord afloat so near the shore that by a stage from her to it all her Cargo might be got out and in again in a very short time; in this same place she might be hove down with all ease, but the beach gave signs of the tides rising in the springs 6 or 7 feet which was more than enough to do our business without that trouble. The meeting with so many natural advantages in a harbour so near us at the very time of our misfortune appeard almost providential; we had not in the voyage before seen a place so well suited for our purpose as this was, and certainly had no right to expect the tides to rise so high here that did not rise half so much at the place where we struck, only 8 Leagues from this place; we therefore returnd on board in high spirits and raisd the spirits of our freinds on board as much as our own by bringing them the welcome news of aproaching security. It blew however too fresh to night for us to attempt to weigh the anchor, I even think as fresh as it has ever done since we have been upon the Coast.

15. Blew all day as fresh as it did yesterday. We thought much of our good fortune in having fair weather upon the rocks when upon the Brink of such a gale. Our people were now however pretty well recoverd from their fatigues having had plenty of rest, as the ship since she was Fotherd has not made more water than one pump half workd will keep clear. At night we observd a fire ashore near where we were to lay, which made us hope that the necessary length of our stay would give us an oportunity of being acquainted with the Indians who made it.

June 16, 1770

Portrait of Charles Green, astronomer

Saturday, 16th. Strong Gales at South-East, and Cloudy, hazey weather, with Showers of Rain. At 6 o'Clock in the A.M. it moderated a little, and we hove short, intending to get under sail, but was obliged to desist, and veer away again; some people were seen ashore to-day.

Banks’ Journal

16. In the morn it was a little more moderate and we attempted to weigh but were soon obligd to vere away all that we had got, the wind freshning upon us so much. Fires were made upon the hills and we saw 4 Indians through our glasses who went away along shore, in going along which they made two more fires for what purpose we could not guess. Tupia whose bad gums were very soon followd by livid spots on his legs and every symptom of inveterate scurvy, notwithstanding acid, bark and every medecine our Surgeon could give him, became now extreemly ill; Mr Green the astronomer was also in a very poor way, which made everybody in the Cabbin very desirous of getting ashore and impatient at our tedious delays.

'Cook’s Endeavour Journal' NLA

Banks and several crewmen had left Matavai Bay in a pinnace to circumnavigate and chart the island of Tahiti. Accompanying them on board was Tupaia, a member of the priestly aristocratic class who had befriended Banks and acted as a guide and adviser during the Endeavour’s stay in Tahiti. Tupaia later joined the ship along with his servant, a Tahitian boy named Taiata. Both would die of dysentery in Batavia.

Yorkshireman Charles Green, assistant to the Astronomer Royal at the Royal Observatory Greenwich joined the voyage to lead the observation of the transit of Venus in Tahiti.

Wikipedia

During Cook's voyage along the coast, he named Green Island, after the astronomer. Green, by this time had contracted scurvy.

The Endeavour was forced to make for Batavia (present-day Jakarta) for repairs (after leaving Cooktown). Disease were rife in the Dutch-controlled city, including malaria and dysentery; Green contracted the latter, dying on 29 January 1771, twelve days after the ship's departure from the port. Cook, in recording Green's death in his log, went on to add that Green had been in ill-health for some time and his lifestyle had contributed to his early death. An account published in a London newspaper described his final hours: "He had been ill some time, and was directed by the surgeon to keep himself warm, but in a fit of phrensy he got up in the night and put his legs out of the portholes, which was the occasion of his death."

“Endeavour” by Peter Aughton

Charles Green, official astronomer was one of the few men alive who could find the longitude at sea purely from observations of the moon and stars. He had crossed the Atlantic in 1763-64 when John Harrison’s fourth marine chronometer was under test. The chronometer was a very expensive instrument then very much in its infancy and was not carried on the Endeavour. It was far too valuable to risk. Cook carried one on his second voyage. Green did not enjoy the best of health. ’He lived in such a manner as greatly promoted the disorders he had long upon him’ wrote Cook. Meaning that he suffered from dysentery and made it worse by drinking. But his bouts were spasmodic.

June 17, 1770

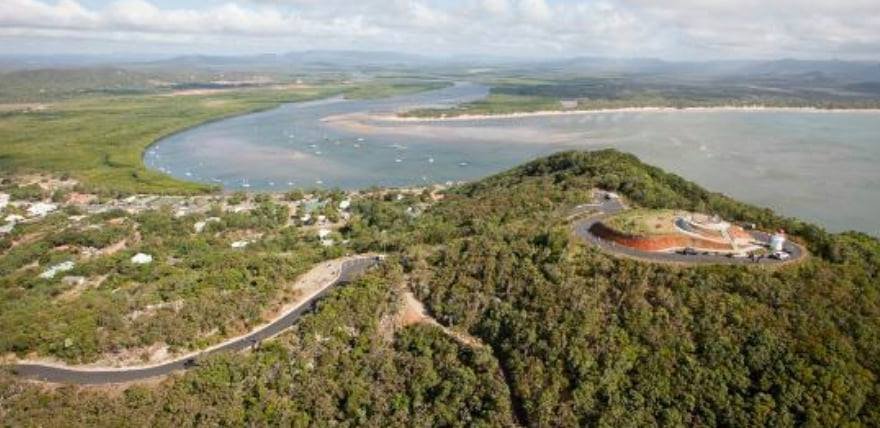

The Endeavour finally entered the harbour of what has become known as Cooktown.

Sunday, 17th. Most part strong Gales at South-East, with some heavy showers of rain in the P.M. At 6 a.m., being pretty moderate, we weigh'd and run into the Harbour, in doing of which we run the Ship ashore Twice. The first time she went off without much Trouble, but the Second time she Stuck fast; but this was of no consequence any farther than giving us a little trouble, and was no more than what I expected as we had the wind. While the Ship lay fast we got down the Foreyard, Foretopmast, booms, etc., overboard, and made a raft of them alongside.

Banks’ Journal

17. Weather a little less rough than it was. Weighd and brought the ship in but in doing it ran her twice ashore by the narrowness of the channel; the second time she remaind till the tide lifted her off. In the meantime Dr Solander and myself began our Plant gathering. In the Evening the ship was moord within 20 feet of the shore afloat and before night much lumber was got out of her.

Cook’s Endeavour Journal” from NLA

Joseph Banks’ assistant was Dr Daniel Solander, among the finest botanists in England and a student of Carl Linnaeus, the founder of modern taxomony. Banks and Solander, a Swede, were helped by the naturalist Herman Spöring a professor of medicine, and by two artists Sydney Parkinson and Alexander Buchan.

Banks had written that ‘no botanist has ever enjoyd (sic) more pleasure in the contemplation of his favourite pursuit than Dr Solander and myself among these plants.’ Thanks to his £6000 a year inheritance Banks was one of Great Britain’s wealthiest men. He had attended Oxford but never graduated. Instead he had learned most of his skills from the man to whom he had paid £400 to accompany him on the voyage, Dr Daniel Solander. The student seemed to have made rapid progress. In 1766 at the age of 23, Banks was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and in the same year he sailed to Newfoundland on his first expedition, to collect birds, animals, rocks and insects.

Solander had studied at Uppsala University in Sweden and was the favourite student of Linnaeus, the famous botanist. In 1760 he sailed to England where he taught the Linnaean system to British naturalists and later joined the staff of the British Museum. Solander met Banks in 1764 and helped his new friend catalogue the specimens from his Newfoundland expedition.

On leaving Botany Bay, named for all the specimens that Banks and Solander collected, Cook named Cape Banks and Point Solander.

In Batavia Solander became dangerously ill and nearly died and Banks grew worse and worse. On 17 December 1770 Taiata died. His fellow countryman Tupaia overcome with grief died three days later. Sydney Parkinson, their esteemed illustrator, died a month after leaving the disease-ridden city.

“Endeavour” by Peter Aughton

Cook thought to call it Sting Ray Harbour, then pondering again that the euphoric botanists engrossed in their great store of new specimens were more characteristic of the place. “The great quantity of New Plants etc Mr Banks & Dr Solander collected in this place occasioned my giving it the name of Botany Bay.”

(On arrival back in England), newspaper stories highlighted the work of Banks and Solander, both noted members of the London salon scene. The two botanists and two of Banks’ servants were the only men of the original group of supernumeraries to survive the voyage and on their return received more publicity than Cook.

Banks and Solander would later sign on to Cook’s second expedition to the South Pacific aboard the Resolution. In the end the ship left without them. Banks had ordered alterations to this collier to accommodate his party of 12, up from 8 on the Endeavour. But his changes had rendered the vessel almost unseaworthy. After the navy ordered that the vessel be restored to its original state, Banks and Solander withdrew from the voyage.

In 1778 seven years after his return on the Endeavour, Banks was elected president of the Royal Society, a position he held until his death 42 years later.

Solander rejoined the staff of the British Museum. He died at 49 in 1782 before he could publish any accounts of his journeys.

June 18, 1770

Monday, 18th. Fresh Gales and Cloudy, with Showers of Rain. At 1 p.m. the Ship floated, and we warped her into the Harbour, and moor'd her alongside of a Steep Beach on the South side; got the Anchors, Cables, and all the Hawsers ashore. In the A.M. made a Stage from the Ship to the Shore, Erected 2 Tents, one for the Sick, and the other for the Stores and Provisions; Landed all the empty Casks and part of the Provisions, and sent a boat to haul the Sean, which return'd without Success.

The Sean is probably the Seine, a net cast for taking fish near the surface.

Peter Aughton in ‘Endeavour’

At first Cook used the journal as a log, recording on the left-hand page information such as wind, course and distance travelled. The dates are written in red ink and the right-hand page is reserved for journal entries. In time these fact-based notes, written in dark ink, were joined by Cook’s descriptions of events and experiences and his thoughts. Cook by his own admission, was not a writer. He would go through several drafts before consigning his words to the pages of his journal and even then would change them again. Cook’s spelling could best be described as perfunctory.it was often phonetic, occasionally reflecting what must have been a strong Yorkshire accent. His punctuation was mostly a stab in the dark.

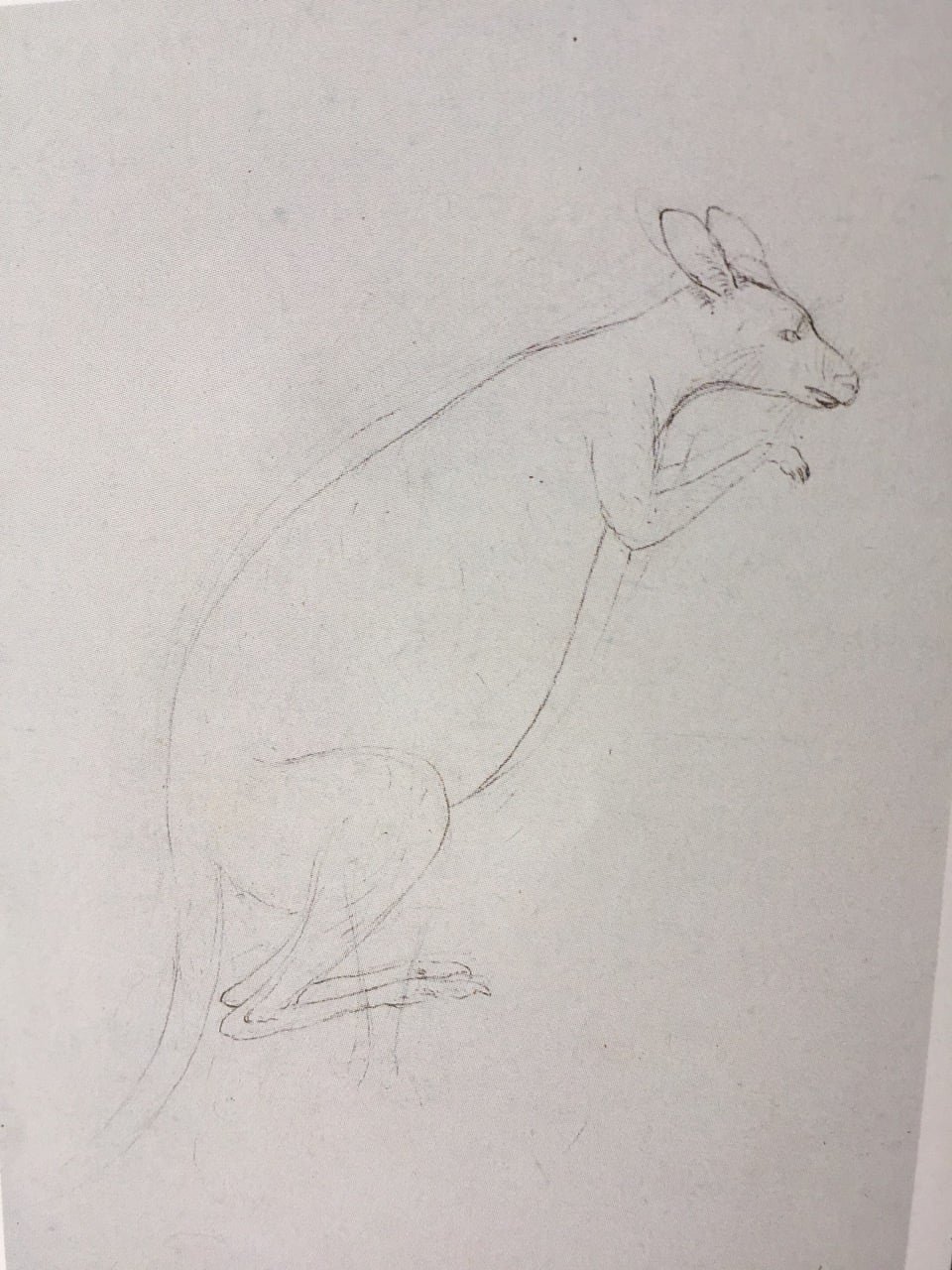

Tents were erected on the bank to house the provisions and the sick. There were nine, including Tupaia who was showing signs of scurvy, and Green the astronomer. Cook worried about the lack of fresh food, sent three men out to shoot pigeons. The men returned with half a dozen and a description of a curious slender animal, smaller than a greyhound, mouse coloured and ‘swift of foot’’. They had seen their first ‘kangaroo’. Cook caught a glimpse of one the next day.

Banks’ Journal